Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world | reviews, news & interviews

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Tate Britain is currently offering two exhibitions for the price of one. Other than being on the same bill, Edward Burra and Ithell Colquhoun having nothing in common other than being born a year apart and being oddballs – in very different ways. And since both reward focused attention, this makes for a rather exhausting outing – I’m reviewing them separately – so gird your loins.

I’ve always been intrigued by Scylla (méditerranée) 1938 (pictured below right) a painting by Ithell Colquhoun that Tate Modern has shown with Surrealists such as Salvador Dali. It’s a double image that, like a “double entendre”, was thought to reveal unconscious or hidden truths.

Colquhoun described it as the view she saw lying in the bath – a triangle of pubic hair and two thighs sticking out of the water. In the painting these are transformed into phallic rocks jutting out of a turquoise sea with a patch of seaweed between them – all portrayed with hallucinatory clarity.

Colquhoun described it as the view she saw lying in the bath – a triangle of pubic hair and two thighs sticking out of the water. In the painting these are transformed into phallic rocks jutting out of a turquoise sea with a patch of seaweed between them – all portrayed with hallucinatory clarity.

Beside it hangs Gouffres Amers (Bitter Abyss) 1939, showing a dead man whose bones are turning into coral while his genitals resemble a sea anemone. He is a spent force and behind him is a rocky arch reminiscent of a vagina that seems to mock his impotence. The power of female sexual energy and its manifestation in nature is a theme that runs through Colquhoun’s work. Foam Flower (1947), for instance, shows a tiny corn on the cob enveloped by fleshy, labial folds that erupt from a crab-like shell nestling among clouds.

She was attracted to both men and women and had visions of a Divine Androgyne in whom the qualities of male and female would be combined. Diagrams of Love 1940-42 (pictured below left, detail) is a series of poems and images – many of which show a central figure surrounded by an aura – in which she envisages this potent sexual and spiritual force.

Inspired by the Surrealists, she began using various kinds of automatism as a way of allowing images to emerge undirected from the unconscious. Decalcomania – covering a surface with paint then pressing another onto it – was a favourite method. The smudgy results would spark ideas that she often clarified with drawn or painted elements, and she even made self-portraits using this technique.

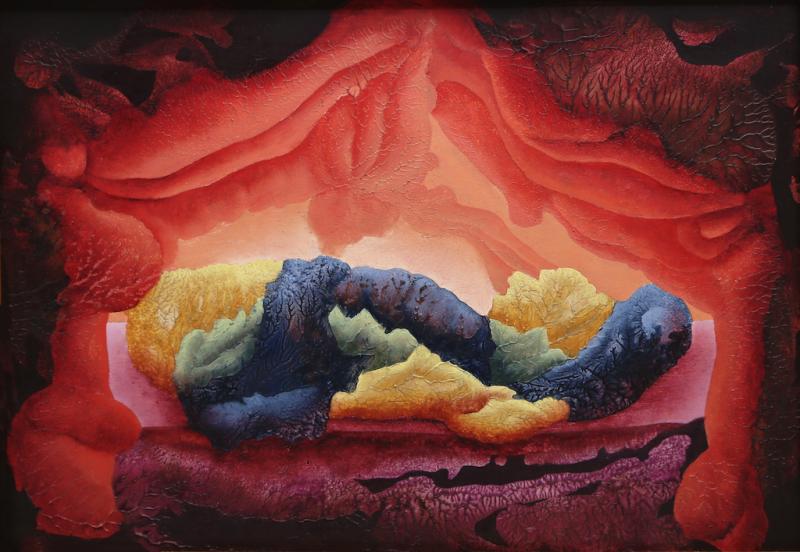

In Dreaming Leaps 1945, the cloudy shapes perform a euphoric aerial dance in front of a clear blue sky, while Alcove 1948 (main picture) is like a vaginal nest or grotto cradling strange, vegetal forms. She also used fumage (creating smoke patterns with a flame) and invented parsemage (dunking paper into water sprinkled with powdered chalk and charcoal).

In Dreaming Leaps 1945, the cloudy shapes perform a euphoric aerial dance in front of a clear blue sky, while Alcove 1948 (main picture) is like a vaginal nest or grotto cradling strange, vegetal forms. She also used fumage (creating smoke patterns with a flame) and invented parsemage (dunking paper into water sprinkled with powdered chalk and charcoal).

Later, in 1977, Colquhoun would use decalcomania to produce a set of Tarot cards in which swirls of enamel paint formed mandala-like bursts of colour. By this time her interest in Surrealism had largely been overtaken by a variety of esoteric and mystical beliefs. She was a member of the Theosophical Society and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, for instance, and after falling out with the Surrealists, who were notoriously sexist and doctrinaire, she moved to Cornwall attracted by the standing stones and other evidence of neolithic sacred sites.

Paintings such as The Sunset Birth 1942 are like diagrams illustrating local myths. It shows three standing stones, the central one perforated by a large hole that was thought to promote fertility and cure infant diseases. Early drawings show a woman threading her way through the hole, but in the final image she is replaced by currents of energy that weave in and around the stones like a cat’s cradle. And inspired by the Merry Maidens stone circle near her home in Paul, Dance of the Nine Opals 1942 (pictured below) refers to a folk story in which a group of women were turned to stone for dancing on the Sabbath.

When she died in 1988 Colquhoun left her archive to the National Trust, which don’t seem to have done much with it. In 2019, they handed over 5,000 artworks to the Tate, which along with the work already donated to them by the artist, creates a substantial holding and makes one think that the gallery could have devoted a full scale exhibition to this intriguing artist.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment