Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute | reviews, news & interviews

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Brian Clarke died on 1 July 2025, after a long illness. He was one of the most original British artists of our time – wide-ranging, ground-breaking and influential. His painting was first-class, but it was in the field of architectural stained glass, which he approached as a fine artist, and in a radically innovative manner, that he truly made a name for himself.

I first met Brian, when I was making a series for BBC Two, “The Architecture of the Imagination” (1994). It was bravely commissioned by Clare Paterson and Alan Yentob, at a time when such off-piste arts explorations were generously funded, shown at 9pm to relatively large audiences, not going for populist packaging, but for adventurous and inspiring content.

The series, built around lengthy interviews with the American writer James Hillman, looked at the symbolic resonances of key architectural features, The Door, The Staircase, The Window, The Bridge and The Tower. The films were packed with extracts from great movies, not least works by Hitchcock, David Lean and Michael Powell, all of whom drew on the archetypal essence behind commonplaces of the building world.

My researcher Sophy Morland found Brian, and he was one of those perfect contributors – as he saw the poetry of the world: there was a poetic sensibility that informed his paintings as much as the extraordinary stained glass he produced for churches, mosques, synagogues, as well as for more secular environments such as shopping arcades and centres, airports and office buildings. Without referencing anything specifically religious, the glass he created always provoked spiritual illumination, whatever the context. In “The Window” segment of the series (link below), Brian talked of his obsessive engagement with windows in his paintings, and his understanding of the role of filtered colour and light in the glass. His account of seeing his father briefly from his bedroom window, as he returned from his regular and lifelong nightshift, is particularly touching.

My researcher Sophy Morland found Brian, and he was one of those perfect contributors – as he saw the poetry of the world: there was a poetic sensibility that informed his paintings as much as the extraordinary stained glass he produced for churches, mosques, synagogues, as well as for more secular environments such as shopping arcades and centres, airports and office buildings. Without referencing anything specifically religious, the glass he created always provoked spiritual illumination, whatever the context. In “The Window” segment of the series (link below), Brian talked of his obsessive engagement with windows in his paintings, and his understanding of the role of filtered colour and light in the glass. His account of seeing his father briefly from his bedroom window, as he returned from his regular and lifelong nightshift, is particularly touching.

Years later, and having become a friend of Brian’s, I made a BBC Four film about him (Colouring Light: Brian Clarke - An Artist Apart, 2011) , which told the story of his life. This and other occasions gave me the opportunity to get to know him better, and most of all the privilege of being on the receiving end of the qualities that poured forth from him, from a lack of illusion about forms of authority, a fabulous and often provocative sense of humour, a very fine intelligence and gift for words, a generosity of spirit that nourished those around him, and an indomitable appetite for creative work – which kept vibrant until his very last days.

There are plenty of obituaries online, and there’s a great website. There, you can find the (amazing) biographical story. I’ll write here more personally.

There are people out there who possess a capacity for channelling the spirit – aka the life force. In the Islamic world, people speak of baraka, something we might translate as grace, blessings or energy from a divine source. Although Brian wasn’t conventionally pious or religious, he understood, in his heart as well as his intellect, the nature of grace and the power of transcendence. There were so many moments with him – such as visiting Salisbury Cathedral where he was discussing a major new window, and visiting St Mary’s in Fairford, Gloucestershire, the home of some of the best medieval stained glass in Britain. He was so inspiring to be with, the joy and wonder he experienced before beauty. It was contagious. In the documentary we made together, there’s a key moment when the Abbess of the small Swiss convent of Romont (pictured above), Mother Marie-Claire, speaks of him with great affection and emotion: "Brian Clarke is someone who has a depth – he may not show it in everyday life, I don’t know him well enough – but what I perceive,” she adds delicately touching her chest, “is that he awakens something in us, something he has within himself, which goes beyond what we can see, reaching towards the invisible.”

In the documentary we made together, there’s a key moment when the Abbess of the small Swiss convent of Romont (pictured above), Mother Marie-Claire, speaks of him with great affection and emotion: "Brian Clarke is someone who has a depth – he may not show it in everyday life, I don’t know him well enough – but what I perceive,” she adds delicately touching her chest, “is that he awakens something in us, something he has within himself, which goes beyond what we can see, reaching towards the invisible.”

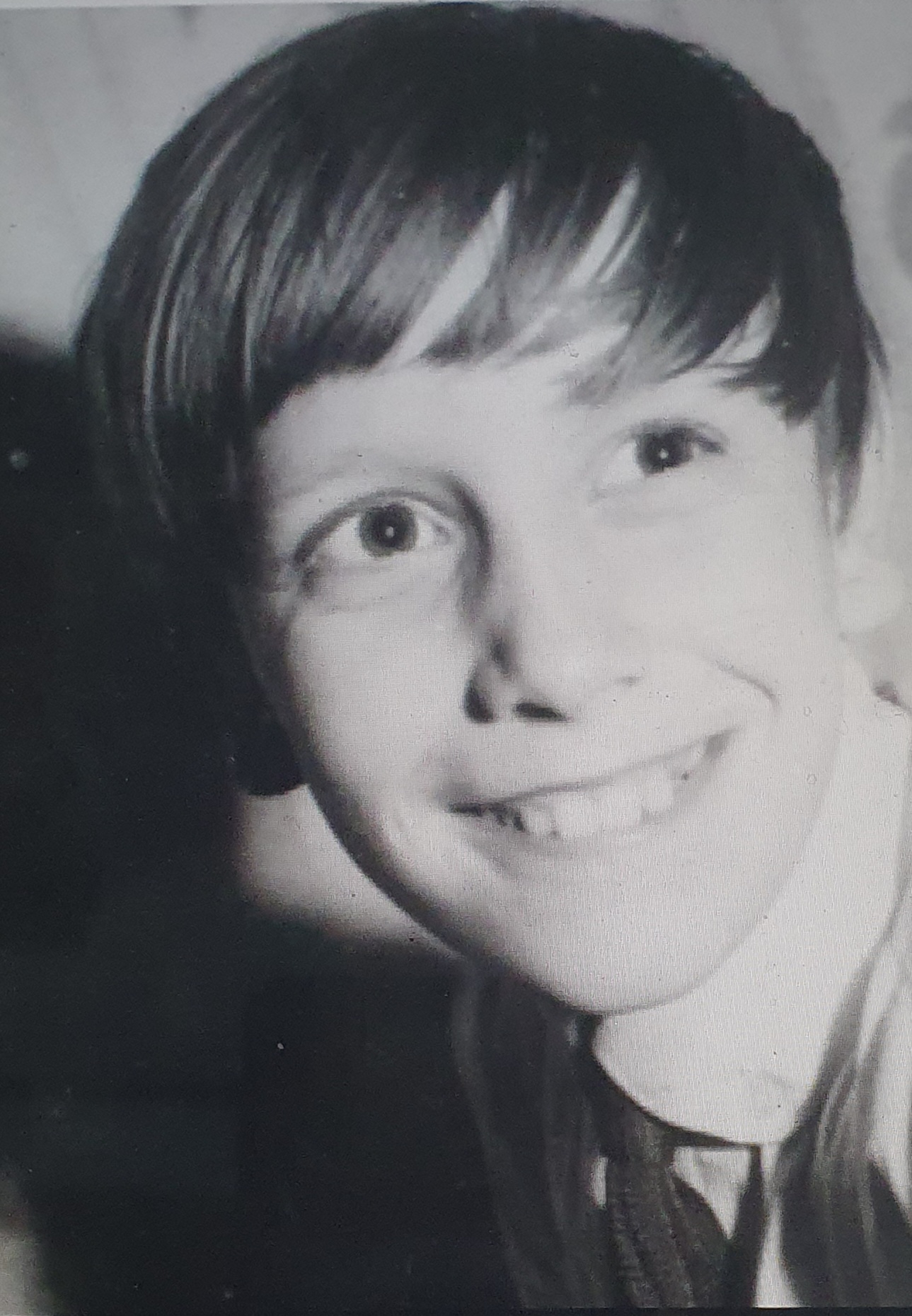

You only have to look at photographs of Brian as a child (pictured below left), and that grace is apparent from the start. The joyful spirit that led him to the Oldham railway station, at the age of 12, where, with coins robbed from a gas metre, he tried to buy a ticket for Paris, where he knew some of the best art was to be found. There was an ambition in Brian, not driven by narcissism – quite the contrary – but by necessity. The work had to be done, this was his calling, and, although his career had its ups and downs, and stained glass was never taken seriously as a form of art, he just kept at it.

Most of all, there was the illumination he felt as a young person when he first set foot in York Minster and was transformed by the combined power of colour and light. Painting was one thing – and he was a very good painter – but the stained glass was where it was at. This was the work that evoked not only the intellect’s joy in form but reached, more seriously, the eye of the heart, the part of us that can be awakened at every moment, not least before the greatest art.

Brian had tons of charisma. There’s a photo online of him being greeted by Queen Elizabeth II, and the glow of joy on her face, as open as can be – almost child-like – is wonderful to behold. Her Majesty is touched by his modest grace, a moment shared by beings whose authenticity shone through superficial appearances. Touched just as much were the rock stars and other celebs who flocked around him from the 60’s on, when Robert Fraser sold his work. I can remember going to Brian’s 40th birthday party. I’m fond of saying that “I was the only person there whom I didn’t recognise!” They were A-listers from the worlds of music, art and architecture. I spent time talking to Brian’s mother, and there was something in her Lancashire spirit that told me a lot about her son’s essential straightforwardness. He was still firmly rooted in his family’s world of factories and mills. I discovered that further when I filmed him on a visit to his native Oldham, where he called on some of his elderly aunts. There was no dutiful local-boy-made-good behaviour calibrated for the camera, but an immensely moving moment of intimacy with these assembled matriarchs, with whom he could be wholly himself, and who revelled in the joy of being with “our Brian”.

Brian had tons of charisma. There’s a photo online of him being greeted by Queen Elizabeth II, and the glow of joy on her face, as open as can be – almost child-like – is wonderful to behold. Her Majesty is touched by his modest grace, a moment shared by beings whose authenticity shone through superficial appearances. Touched just as much were the rock stars and other celebs who flocked around him from the 60’s on, when Robert Fraser sold his work. I can remember going to Brian’s 40th birthday party. I’m fond of saying that “I was the only person there whom I didn’t recognise!” They were A-listers from the worlds of music, art and architecture. I spent time talking to Brian’s mother, and there was something in her Lancashire spirit that told me a lot about her son’s essential straightforwardness. He was still firmly rooted in his family’s world of factories and mills. I discovered that further when I filmed him on a visit to his native Oldham, where he called on some of his elderly aunts. There was no dutiful local-boy-made-good behaviour calibrated for the camera, but an immensely moving moment of intimacy with these assembled matriarchs, with whom he could be wholly himself, and who revelled in the joy of being with “our Brian”.

It’s not surprising that the team at his Acton studio tended to stay there for years and years. They were devoted to Brian, and infected by the spirit that drove him. He was a wonderful leader, but never a tyrant. The affection he had for his team was always a joy to behold. Visits to the studio were always a great pleasure, from which one came away with a new and deeply felt lease of life. That energy was in the work too, of course, even when he tackled mortality as he has done in so much of his work. But it was never morbid, always at the service of the divine mystery, in which death (and constant rebirth) play an essential part.

Much of the last work Brian made, during his long illness, which he bore with such courage, consisted of colourful collages of flowers. Like Matisse in his last months, he couldn’t let go of the celebration of life’s gifts to us, and nature’s beauty. His final one-man show at the Newport Street Gallery (2023), was a triumph, the flower collages covering an entire wall and communicating a joy that will continue to nourish us, beyond the doubt, the grief, the pain we suffer. He remains someone whose wise understanding that suffering and joy are inextricably linked will stay with me. At the heart of that wisdom, there’s the acknowledgment that love is what connects everything, and that we may give and receive it in a manner that constantly enriches the world.

Watch an extract from "The Window", Episode 3 of The Architecture of the Imagination (BBC2, 1994) in which Brian Clarke talks about a window in his Oldham bedroom and the transcendent magic of stained glass in general. The films in the series were made in collaboration with James Hillman and Susan Kidel. Music courtesy of Brian Eno, whom we used extensively and to great effect throughout the series.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment