Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world | reviews, news & interviews

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

It took until the last room of her exhibition for me to gain any real understanding of the work of Australian Aboriginal artist Emily Kam Kngwarray. Given that Tate Modern’s retrospective of this highly acclaimed painter comprises some 80 paintings and batiks, the process had been slow!

Gazing at Winter Awely I 1995, (pictured right) the very last painting in the show, I was suddenly transported back to the Northern Territories, north east of Alice Springs, where Kngwarray lived and worked and which I visited many years ago. Strings of dots cascade down the canvas. White, yellow, orange and green, they hover over a deep crimson ground like necklaces dangling in the wind.They seem to dance in front of your eyes, going in and out of focus as though in a heat haze and inducing the same sense of light headedness as the insufferable heat. The effect is hallucinatory, transporting – as if you are about to faint. Nothing feels stable; there’s nothing to hang onto.

Gazing at Winter Awely I 1995, (pictured right) the very last painting in the show, I was suddenly transported back to the Northern Territories, north east of Alice Springs, where Kngwarray lived and worked and which I visited many years ago. Strings of dots cascade down the canvas. White, yellow, orange and green, they hover over a deep crimson ground like necklaces dangling in the wind.They seem to dance in front of your eyes, going in and out of focus as though in a heat haze and inducing the same sense of light headedness as the insufferable heat. The effect is hallucinatory, transporting – as if you are about to faint. Nothing feels stable; there’s nothing to hang onto.

Written on the wall is a comment made by the artist’s kinswomen, Jedda Purvis Kngwarray and Josie Petyarr Kngwarray. ‘If you close your eyes and imagine the paintings in your mind’s eye, you will see them transform,” it says. “What Kngwarray painted is alive and true. The paintings are dynamic and keep changing.”

Hanging nearby, Mern Bush Tucker 1995 consists of looping lines in pale pink, crimson and grey over a burnt-orange ground. It’s like peering into tangled blades of the woollybutt grass that grows in the area. Untitled 1996 is even more striking. Thick brushstrokes in white and purple sweep across a dark brown ground. It reminds me of the gestural abstraction of postwar French painters like Hans Hartung and Pierre Soulages, but to hail Kngwarray as an abstract artist, as many have done, is to miss the point.

Kngwarray painted sitting on the ground with the canvas spread out in front of her, sometimes using brushes, sometimes fingertips – as if she were recounting myths while drawing in the red sand. Her pictures are not an ego trip, then; this is not abstract expressionism but story telling. They elucidate the knowledge gained in The Dreaming, a mythological realm in which time is fluid and ancestral beings reveal the interconnectedness of all things. They describe her place in a complex web of relations that includes people, animals, plants and place.

Kngwarray painted sitting on the ground with the canvas spread out in front of her, sometimes using brushes, sometimes fingertips – as if she were recounting myths while drawing in the red sand. Her pictures are not an ego trip, then; this is not abstract expressionism but story telling. They elucidate the knowledge gained in The Dreaming, a mythological realm in which time is fluid and ancestral beings reveal the interconnectedness of all things. They describe her place in a complex web of relations that includes people, animals, plants and place.

Having begun to get a sense of the pictures, I return to the beginning of the exhibition which is in chronological order. Kngwarray was already in her mid sixties when she joined the Utopia Women’s Batik Group, an initiative set up to provide employment for women in this impoverished region.

Dating from the early 1980s, her very beautiful designs echo the sand paintings made by women as they recount stories from The Dreaming. Some are like diagrams mapping journeys, others are like inventories of the flora and fauna found in Alhalker Country. Lizards, snakes, centipedes and emu footprints appear among the trailing vines of the pencil yam, whose roots are edible and whose seeds and seed pods – after which Kngwarray was named Kam – are represented by myriad dots.

In 1988, she began painting and in her first picture Emu Woman (pictured above left) one can make out the body of a woman decorated with traditional, awely patterns in readiness for ceremonial dancing and singing.

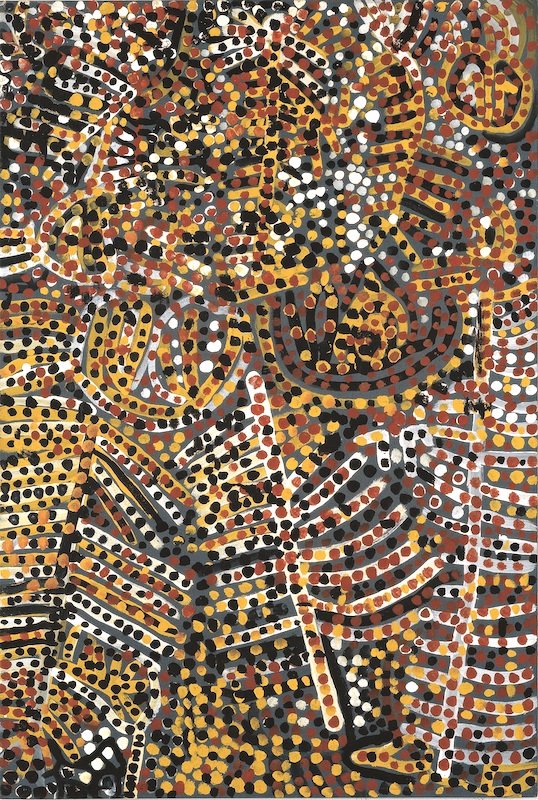

The myriad layers of dots in Kam 1 1991 (main picture) refer to the seeds and pods of the pencil yam at various stages of maturity. In other pictures they capture the profusion of seeds of woollybutt grass and the flowers that carpet the arid land after rain.

The most impressive aspect of the Australian landscape is its enormous scale and the deserts of Alhalker – Kngwarray’s country – can seem like a vast expanse of boundless space with no landmarks to provide orientation. With its all-over composition, glorious paintings like Mern angerr 1992 (pictured above) capture both the dazzling heat and that sense of disorientation. Its mesmerising overlay of dots in pinks, yellows, ochres, oranges, greens and lilac is like a portrait of this vast land; while describing the flora, it also evokes the experience of being immersed in heat, light and dust, and of being in deep connection with one’s place of origin.

The most impressive aspect of the Australian landscape is its enormous scale and the deserts of Alhalker – Kngwarray’s country – can seem like a vast expanse of boundless space with no landmarks to provide orientation. With its all-over composition, glorious paintings like Mern angerr 1992 (pictured above) capture both the dazzling heat and that sense of disorientation. Its mesmerising overlay of dots in pinks, yellows, ochres, oranges, greens and lilac is like a portrait of this vast land; while describing the flora, it also evokes the experience of being immersed in heat, light and dust, and of being in deep connection with one’s place of origin.

While painting these larger pictures, Kngwarray would often sit in the middle of the canvas; so there's no top or bottom, just all-encompassing space. Works may be displayed and reproduced in different orientations; the reproduction of Kam I, for instance, is offered to the press in landscape format while at Tate Modern the picture is hung vertically. This is not a mistake since, although the paintings are in a sense landscapes, they are not about looking at a view but being immersed in a place; they convey a somatic experience rather than a visual sensation – being rather than seeing. In 1993, she changed tack and began painting lines representing the stems and roots of the pencil yam – after which she was named and which defined her identity as a member of her community – as well as the lines drawn in earth pigments onto women’s bodies for ceremonial dances. With its emphatically repeated lines, Untitled awely 1994 (pictured above) is, then, a kind of self-portrait, a declaration of identity and belonging – clear, direct and affirmative.

In 1993, she changed tack and began painting lines representing the stems and roots of the pencil yam – after which she was named and which defined her identity as a member of her community – as well as the lines drawn in earth pigments onto women’s bodies for ceremonial dances. With its emphatically repeated lines, Untitled awely 1994 (pictured above) is, then, a kind of self-portrait, a declaration of identity and belonging – clear, direct and affirmative.

- Emily Kam Kngwarray is at Tate Modern until 11 January 2026

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment