Till the Stars Come Down, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - a family hilariously and tragically at war | reviews, news & interviews

Till the Stars Come Down, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - a family hilariously and tragically at war

Till the Stars Come Down, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - a family hilariously and tragically at war

Beth Steel makes a stirring West End debut with her poignant play for today

The 2024 play at the National Theatre that put writer Beth Steel squarely centre-stage has now received a West End transfer. Its title taken from an Auden poem urging people to dance till they drop, it’s probably the most passionate show in that locale, and definitely the lewdest.

It opens with the female equivalent of locker-room talk as the women of an extended family in what was once Notts and Derby pit country bicker and banter while preparing for the wedding of young Sylvia (Sinead Matthews). Topics of conversation range from the naughtiness of next door’s "sex pond”, ie hot tub, to the lamentable greying of pubic hair. Sylvia is marrying a Pole, Marek (Julian Rostov), who has worked his way up from Megabus migrant to local businessman. In an area where unemployment is rampant, Marek could be a sign of hope and renewal.

Not that the family he is marrying into uniformly sees him that way. His main detractor is Hazel (Lucy Black, pictured below right), fierce mother of two young girls and a surrogate mother to Sylvia, her sister Linda’s child. Linda has died of an unnamed disease that one assumes was a cancer the doctor didn’t spot in time. Hazel’s husband John (Adrian Bower) is an unemployed former miner, and she reluctantly works for the main local employer, a distribution warehouse. Her outlook is dogged by the Eastern European immigrants who work there and, she believes, “look after their own”, blocking her promotion. Also present is Hazel’s other sister, multiply married Maggie (Aisling Loftus), now on her own, who had moved to London six months earlier.

The life and soul of this particular party is Aunty Carol (Dorothy Atkinson, pictured left), married to Uncle Pete (Philip Whitchurch), another former miner, who has been on the outs with Sylvia’s father, his brother Tony (Alan Williams), for 37 years. Carol is an "I’m-mad-me" extrovert who fuels the wedding celebrations with her numerous ribaldries. Soon all the ingredients for a right royal family barney, a speciality of many a wedding, are in place.

The life and soul of this particular party is Aunty Carol (Dorothy Atkinson, pictured left), married to Uncle Pete (Philip Whitchurch), another former miner, who has been on the outs with Sylvia’s father, his brother Tony (Alan Williams), for 37 years. Carol is an "I’m-mad-me" extrovert who fuels the wedding celebrations with her numerous ribaldries. Soon all the ingredients for a right royal family barney, a speciality of many a wedding, are in place.

What Steel does well is to disguise the main focus of her play for most of the first half. We are drawn into the bantering preparations, the makeup tips, the panic when Sylvia’s dress doesn’t fit, all the conventional goings-on. These women are wildly entertaining: viciously, instinctively witty and plain-spoken, yet practised at finding unusual analogies. Maggie says she was once attracted to a man who looked at her as if she were a potato in a famine. Hazel remarks that when she first saw a Polish name, she thought, “That’s not a name, it’s a wifi password.” The good cheer is extended to the audience, who get to sing a daft song with Marek, after he has shaken the hands of those in the front row of the onstage seating.

A darker element creeps in when it starts to become clear that Maggie and John are inappropriately close. There’s also a frisson between Tony and Carol when she adjusts his tie for him. As the alcohol levels rise, inhibitions go, people are discovered in compromising situations, the family groupings are disturbed. Hazel’s daughter Leanne, a newly converted vegetarian with growing climate concerns, ends the first act by predicting the end of the world. Her pronouncement seems overblown, but it’s horribly ironic coming from the child of a community built on mining fossil fuels, and a sign of the widening rifts between the generations, as well as the genders.

What follows in the second half is an end-of-days scenario of a different order. The alcohol has also encouraged pent-up anger and unhappiness to erupt. We duly learn what the source of Tony and Pete’s feud is, and it isn’t purely domestic, but a fault line running through their whole world. Sylvia’s wedding simultaneously prompts notions of closer ties but also a reopening of old wounds. The whole builds to a bitter, howling climax.

What follows in the second half is an end-of-days scenario of a different order. The alcohol has also encouraged pent-up anger and unhappiness to erupt. We duly learn what the source of Tony and Pete’s feud is, and it isn’t purely domestic, but a fault line running through their whole world. Sylvia’s wedding simultaneously prompts notions of closer ties but also a reopening of old wounds. The whole builds to a bitter, howling climax.

The design of the piece is like something from a sports field, a big white O on green flooring that serves as both a suggestion of a tight family circle and a ring for combat. A glitterball overhead moves in and out of the action, but the exuberant dancing the cast perform under it evolves into serious fighting. Similarly, Paule Constable’s lighting switches the mood from partying fun to sinister black shadows and back.

Half the original cast have moved up west with the piece, notably Sinead Matthews and Lucy Black, twin captains of opposing factions. Matthews is, as ever, a ball of energy, her distinctive low throaty voice modulating strikingly between humour and spitfire retorts. Black, too, puts her foot to the floor and from comically wriggling out of her Spanx (duly thrown into the audience) at the disco, turns into an icily angry heroine worthy of Euripides.

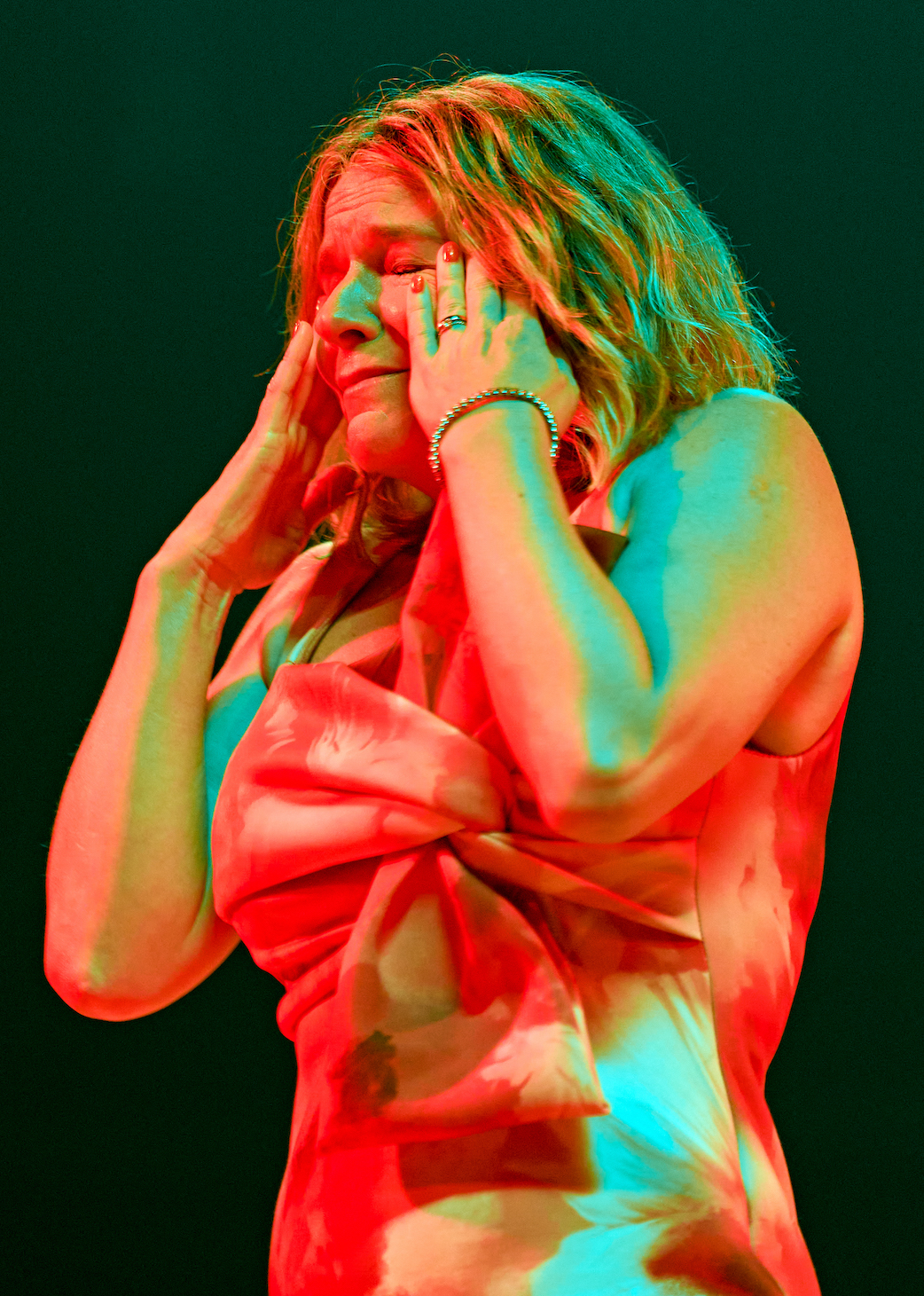

All the cast are in the grip of an unusual energy that sends them scurrying around the set in perfectly choreographed moves. Even Marek joins in, stopping to do a mad exercise routine, part squat, part clownish side bends, before ploughing into the buffet. Atkinson gets the most laughs: her drunken solo dance is hilarious, an unleashed blend of disco and bump’n’grind. But when she deflates, shocked by something she has seen, a palpable sadness takes over her features. It’s one of the juiciest roles for an actress in town.

Director Bijan Sheibani steers this ensemble through the play’s patches of chaos and pathos with exemplary control. Those two modes are echoed in the clever incidental music – souped up snatches from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons – which gives the piece a faux bounciness, even as it slowly grabs you round the throat. The women may seem to rule this territory now, their menfolk frozen by unemployment, but both sexes are victims of forces in the wider world, and their need to present a united front has never been greater. Which makes the final scene of this blistering play for today one of the saddest in the West End, too.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Add comment