The Queen of Spades, Garsington Opera review - sonorous gliding over a heart of darkness | reviews, news & interviews

The Queen of Spades, Garsington Opera review - sonorous gliding over a heart of darkness

The Queen of Spades, Garsington Opera review - sonorous gliding over a heart of darkness

Striking design and clear concept, but the intensity within comes and goes

Recent events have prompted the assertion – understandable in Ukraine – that the idea of the Russian soul is a nationalist myth. This production reminded me that it isn’t, if only by telling us of what we’ve lost: the majority of those great Russian singers and conductors who lit up previous stagings of Tchaikovsky’s dark masterpiece.

Though Jack Furness’s period-conscious concept – no violations pushed too far as in Stefan Herheim's Royal Opera horror – works beautifully with Tom Piper’s endlessly resourceful designs, Lizzie Powell’s lighting and Lucy Burge’s quirky choreography, the musical values at Garsington don’t go deep or soulful enough.

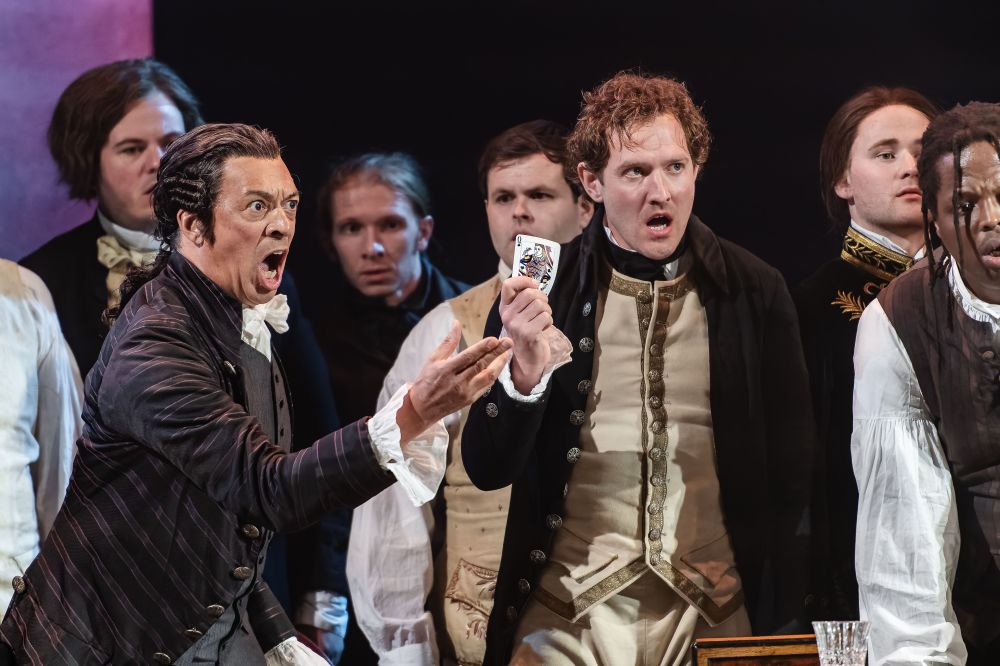

Herman, Tchaikovsky's and Pushkin's outsider figure whose rational Germanic side – in the lean short story, he tells gambling officers "I am not in a position to sacrifice the necessary in the hope of acquiring the superfluous" – is overwhelmed by a growing obsession to learn the secret of three winning cards from an ancient Countess, needs a singing actor convincing in the character's growing madness. Aaron Cawley is only fitfully that. He has the money notes, culminating in the untransposed aria with its taxing long-held top B right at the end (Tchaikovsky provides an alternative transition to a tone lower, which many singers take).  Cawley can also sing softly, crucially so in the climactic scene where Herman confronts the Countess in her bedchamber. But the unrelenting tension isn't there: we see and hear it in the desolation of Sam Furness's Chekalinsky, whom Herman beats at the gambling table with two of his three supposedly winning cards (Furness pictured above with the "losing" card and with Roderick Williams' Yeletsky left). All eyes are on Furness here. And does the intimacy of Garsington in any case need an heroic tenor? A singer with an emphasis on the lyric, like Georgi Nelepp in the classic recording which was my BBC Radio 3 Building a Library choice many years ago, might work better here.

Cawley can also sing softly, crucially so in the climactic scene where Herman confronts the Countess in her bedchamber. But the unrelenting tension isn't there: we see and hear it in the desolation of Sam Furness's Chekalinsky, whom Herman beats at the gambling table with two of his three supposedly winning cards (Furness pictured above with the "losing" card and with Roderick Williams' Yeletsky left). All eyes are on Furness here. And does the intimacy of Garsington in any case need an heroic tenor? A singer with an emphasis on the lyric, like Georgi Nelepp in the classic recording which was my BBC Radio 3 Building a Library choice many years ago, might work better here.

Sadly the lead soprano doesn't offer any chemistry with her tenor either. Laura Wilde is statuesque, but her dramatic reactions are underpowered even if most of her top notes aren't, and she sings seriously flat in places. You can't believe in the sexual attraction of the second scene, nor in Lisa's desperation by the Winter Canal, the weakest stretch of this production. Her partner in the pretty period duet, Stephanie Wake-Edwards as the Princess Polina, shows us what a difference genuine reactions make; like Furness the tenor (brother of the director), she pulls focus far more effectively (Wake-Edwards pictured below on the left with Wilde).  Robert Hayward has stature as Count Tomsky, who narrates the story of the Countess's racy past, but now finds some of the high notes taxing. Roderick Williams, surprisingly, has a few tuning problems but makes the beautiful aria of Yeletsky, the betrothed Lisa doesn't love, affecting. Last night Diana Montague was indisposed, so we had her cover as the Countess. Harriet Williams may not look like a mysterious relic, but she sang the Gretry aria before sleep overcomes the old woman with perfect quiet tones; the magic you need here, where you could hear a pin drop in the audience, certainly cast its spell even if the scene could have been darker and more atmospheric.

Robert Hayward has stature as Count Tomsky, who narrates the story of the Countess's racy past, but now finds some of the high notes taxing. Roderick Williams, surprisingly, has a few tuning problems but makes the beautiful aria of Yeletsky, the betrothed Lisa doesn't love, affecting. Last night Diana Montague was indisposed, so we had her cover as the Countess. Harriet Williams may not look like a mysterious relic, but she sang the Gretry aria before sleep overcomes the old woman with perfect quiet tones; the magic you need here, where you could hear a pin drop in the audience, certainly cast its spell even if the scene could have been darker and more atmospheric.

Elsewhere, the production team works wonders. Side curtains can be pulled across when the beautiful Garsington scene either side of the wonderful pavilion needs shutting out, which of course it doesn't for the opening scene in St Petersburg's Summer Gardens on a fine May afternoon. Furness provides a few telling touches where Tchaikovsky provides imperial divertissement of the highest order: one of the boy soldiers in the homage to the ragamuffin-accompanied guard-changing in the composer's favourite opera, Bizet's Carmen, is bullied by the others – a parallel to Herman's treatment at the hands of the officers. Chamber scenes work well on a platform pulled forward between the big mirrors, and their arrangement in a long line functions for the stretch of canal in Act Three.  Lucy Burge's dancers enrich the action in the usually overstretched party scene (pictured above), even if it does at times seem more brothel than grand St Petersburg mansion, and the Mozartian pastiche of "The Faithful Shepherdess" both looks pretty and is enhanced by Lisa and Polina playing the pastoral lovers' roles. Herman's weird behaviour is enhanced here and in the appearance of Catherine the Great, presumably a fantasy since he shoots her at the slightly awkward end of the first half. She's not, as I at first wondered, the same performer as the dancer-actor playing the young and beautiful Countess of the Jeu de la Reine in Paris (Sophie Tierney, who should have been credited), a very effective figure who becomes the portrait of the "Muscovite Venus" in her older version's room.

Lucy Burge's dancers enrich the action in the usually overstretched party scene (pictured above), even if it does at times seem more brothel than grand St Petersburg mansion, and the Mozartian pastiche of "The Faithful Shepherdess" both looks pretty and is enhanced by Lisa and Polina playing the pastoral lovers' roles. Herman's weird behaviour is enhanced here and in the appearance of Catherine the Great, presumably a fantasy since he shoots her at the slightly awkward end of the first half. She's not, as I at first wondered, the same performer as the dancer-actor playing the young and beautiful Countess of the Jeu de la Reine in Paris (Sophie Tierney, who should have been credited), a very effective figure who becomes the portrait of the "Muscovite Venus" in her older version's room.

Conductor Douglas Boyd seems most at home in the Mozart element; the darker undertow isn't always apparent, though the Philharmonia woodwind relish Tchaikovsky's increasingly grotesque scoring for them. The chorus is splendid in their division of labours, above all the men, who make the orthodox chorus at the end moving. A pleasurable evening, but not exactly one to make the flesh creep as Tchaikovsky and Pushkin wanted.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Add comment