Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows | reviews, news & interviews

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Sometimes, as the first act of Beethoven’s Fidelio closes, the chorus of prisoners discreetly fade away backstage as their brief taste of liberty ends. At Garsington Opera, in Jamie Manton’s revival of a production by John Cox, they slowly descended, one by one, through a circular trap at the front of the stage. We see and hear freedom’s loss, person by person, step by agonising step.

Then I strolled out onto the Garsington terrace as the evening sun set with its midsummer languor over the Wormsley estate’s vast acres of lake, woods and grazing deer. And thought, as Beethoven insisted we must, of all the tormented captives still in all the lightless dungeons of all the tyrants of the world.

Garsington’s airy and luminous opera pavilion challenges any interpreter of a work so filled – dramatically and musically – with the subterranean darkness of buildings, of institutions, and of the human soul. But it is also bathed in the radiance of hope, as the faithful Leonore (disguised as Fidelio) plans and works to release her husband Florestan from unjust imprisonment in Don Pizarro’s fortress jail.  Manton’s renewal of Cox’s version made the summer light that floods this venue an ally of the hope that flickers fitfully in the first act. In the second, the gloom deepens, but now the glow of redemption emanates from within. In the pit, Garsington’s artistic director Douglas Boyd conducted not a conventional Beethovenian band but Baroque specialists The English Concert, whose period-instrument soundscape added its distinctive flavours to the sensory mix.

Manton’s renewal of Cox’s version made the summer light that floods this venue an ally of the hope that flickers fitfully in the first act. In the second, the gloom deepens, but now the glow of redemption emanates from within. In the pit, Garsington’s artistic director Douglas Boyd conducted not a conventional Beethovenian band but Baroque specialists The English Concert, whose period-instrument soundscape added its distinctive flavours to the sensory mix.

At first, for those used to claustrophobic and dimly-lit Fidelios, the brilliant open spaces here can disconcert. Gary McCann’s design makes the prison a semicircular lattice of cages and walkways dominated by a central observation tower. We initially enter not the dripping black stones of traditional confinement, but the metallic security architecture and intrusive 24/7 surveillance of “correctional” facilities and war-zone border-posts today. Meanwhile, those prominent front-stage traps hint at the unseen, redacted horrors underneath.

Isabelle Peters’s Marzelline, daughter of the decent but cowed jailer Rocco (pictured above), gardens busily in the courtyard – an early nod to yearnings for light, and growth. As Oliver Johnston’s robust and engaging Jaquino tries to woo her, and she reveals her devotion to the mysterious prison helper Fidelio, the fierce light and bare stage expanses sometimes dwarfed the cast’s quest for authentic domesticity in these opera buffa scenes. Naked power, and those ever-looming grids, overwhelm fragile human feelings. Still, Peters’s soprano lent Marzelline heft and zest as well as lyric elegance, while the well-rounded generosity of Jonathan Lemalu’s bass (pictured below with Musa Ngkungwana, right) gave Rocco the charm and (bumptious) confidence he can express when safely out of sight of the oppressor class.  The crucial spoken passages of this Singspiel came over clearly, the cast's German diction precise, while Sally Matthews’s Leonore/Fidelio acted with authority before she sang a solo word. Still, we quickly sensed her power and range in the quartet, “Mir ist so wunderbar”, and trio, “Gut Sönnchen gut”. Musa Ngqungwana’s forcefully creepy Pizarro – impressively nasty in “Ha! Welch ein Augenblick” – made vividly clear his lethal intentions towards Florestan. Matthews’s impassioned recitative “Abscheulicher, wo eilst du hin” saw her roam in anguish about the wide stage as her voice spanned equal emotioal extremes. Then her radiant “Komm Hoffnung” summoned calm hope, and light, again. Early on, Matthews (pictured below) occasionally sang with more force than grace. But in due course, vocal assurance matched a riveting stage presence and the ability – in the pivotal ensemble set-pieces – to cut through surrounding walls of sound with a blazing fervour.

The crucial spoken passages of this Singspiel came over clearly, the cast's German diction precise, while Sally Matthews’s Leonore/Fidelio acted with authority before she sang a solo word. Still, we quickly sensed her power and range in the quartet, “Mir ist so wunderbar”, and trio, “Gut Sönnchen gut”. Musa Ngqungwana’s forcefully creepy Pizarro – impressively nasty in “Ha! Welch ein Augenblick” – made vividly clear his lethal intentions towards Florestan. Matthews’s impassioned recitative “Abscheulicher, wo eilst du hin” saw her roam in anguish about the wide stage as her voice spanned equal emotioal extremes. Then her radiant “Komm Hoffnung” summoned calm hope, and light, again. Early on, Matthews (pictured below) occasionally sang with more force than grace. But in due course, vocal assurance matched a riveting stage presence and the ability – in the pivotal ensemble set-pieces – to cut through surrounding walls of sound with a blazing fervour.

As for the first prisoners’ chorus, Manton and McCann enlisted the Chiltern sunlight, and sunset, perfectly. They made “O welche Lust” a transcendent hymn to freedom and nature. During their truncated liberation, the captives stumbled through the pavilion’s open west side to enjoy the Garsington gardens. Always impressive, the formidable house chorus – directed by Jonathon Cole-Swinard – brought gravity and passion to this iconic scene.  Before the second act, The English Concert’s intermezzo had a bracing snap and drive that we hadn’t always heard in the first. The overture, Beethoven’s final of four versions, had sounded a trifle lacklustre, but later strong, bold accents came into play from horns (led by Ursula Paludan Monberg), cellos, trumpets, flutes – and Rachel Chaplin’s soaring oboe. As the external light faded and blinds blocked the pavilion’s open sides, Florestan’s pit of despair took on a scarily physical form. Chained in his pipe-like isolation cell – those chains snaked and rattled through this Fidelio – he sang from the place of concealed darkness that all repressive systems, however modern and transparent, hide. Although the costumes mostly suggested the opera’s own era (first 1805, then 1814), the production aimed to evoke the timeless dynamics of oppression, complicity, courage and resistance.

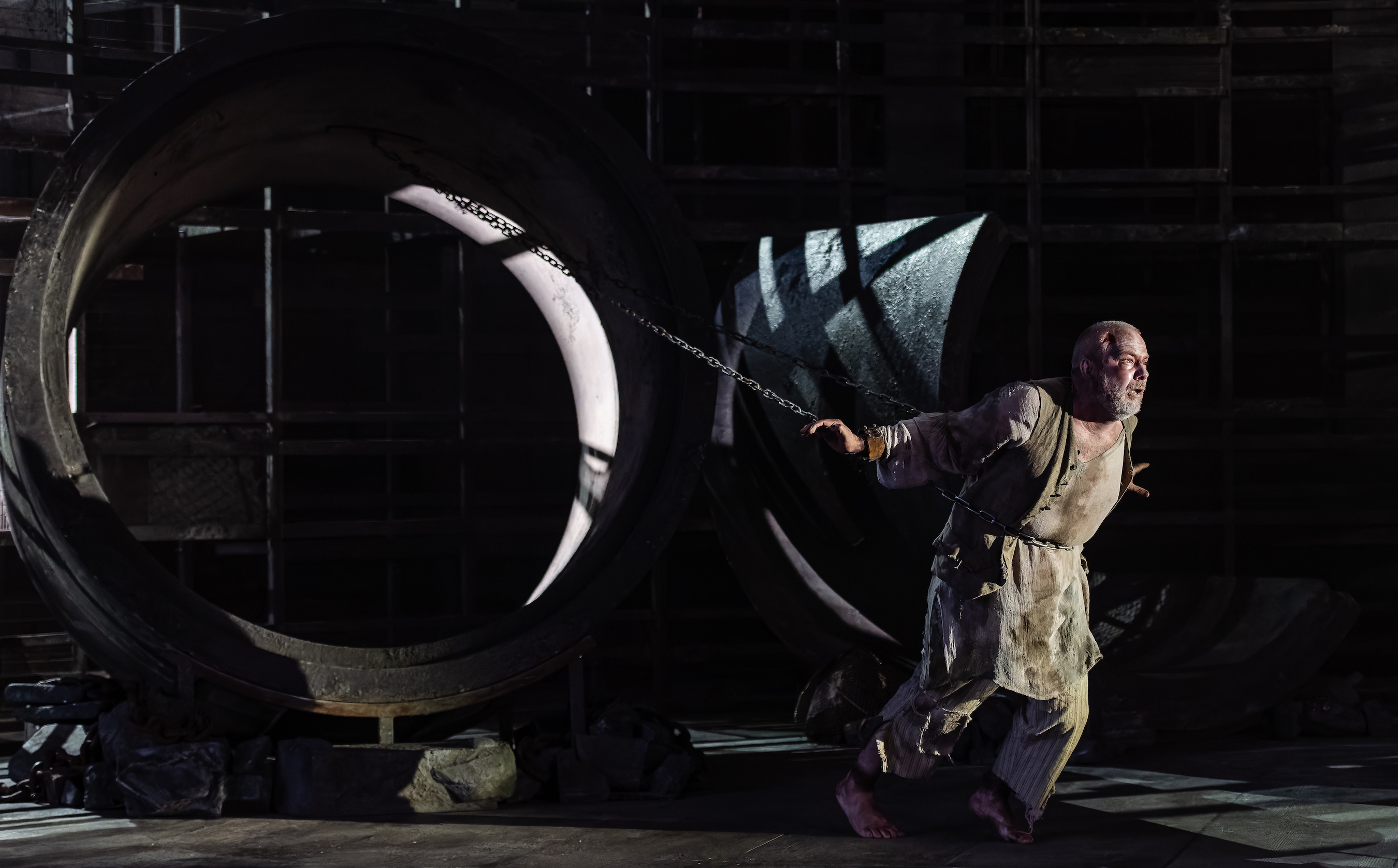

Before the second act, The English Concert’s intermezzo had a bracing snap and drive that we hadn’t always heard in the first. The overture, Beethoven’s final of four versions, had sounded a trifle lacklustre, but later strong, bold accents came into play from horns (led by Ursula Paludan Monberg), cellos, trumpets, flutes – and Rachel Chaplin’s soaring oboe. As the external light faded and blinds blocked the pavilion’s open sides, Florestan’s pit of despair took on a scarily physical form. Chained in his pipe-like isolation cell – those chains snaked and rattled through this Fidelio – he sang from the place of concealed darkness that all repressive systems, however modern and transparent, hide. Although the costumes mostly suggested the opera’s own era (first 1805, then 1814), the production aimed to evoke the timeless dynamics of oppression, complicity, courage and resistance.

In his rags, the archetypal victim of injustice, Robert Murray’s Florestan (pictured below) conjured awesome reserves of power for the crescendo that launches his great cry from the depths, “Gott! Welch Dunkel hier!” Having suffered Tobias Kratzer’s ludicrous semi-abstract botch of the dungeon scenes in Covent Garden’s Fidelio last year, I gave thanks for this plausibly foul and freezing oubliette. From the off, Murray’s heroic tenor projected authority and resilience: a musical treat, although another sort of reading might have called for a frailer, more vulnerable voice. Before Fidelio saves her husband from the secret murder Pizarro intends, Lemalu’s Rocco allowed the jailer’s gruff integrity to surface in his exchanges with the intrepid wife. Matthews only grew in authority and impact. When the moment of discovery and reunion came, her duets with Murray – above all “O namenlose Freude” – had an almost desperate, frantic edge, their exquisitely interwoven lines threaded with panic at further loss as much as joy.

Before Fidelio saves her husband from the secret murder Pizarro intends, Lemalu’s Rocco allowed the jailer’s gruff integrity to surface in his exchanges with the intrepid wife. Matthews only grew in authority and impact. When the moment of discovery and reunion came, her duets with Murray – above all “O namenlose Freude” – had an almost desperate, frantic edge, their exquisitely interwoven lines threaded with panic at further loss as much as joy.

For the finale, as Richard Burkhard’s sweetly stern Don Fernando arrived to deliver justice and correct Pizarro’s abuses, Manton moved into another, more stylised mode. The ceremonial climax, which directors may skimp or twist, became a solemn ritual of white-robed Enlightenment. Angelic (or maybe vestal) attendants serenely held candles on those grim walkways. Minister Fernando laid down the law as a Sarastro-like figure, aloft on the observation tower while he spread a wisdom that felt as much mystical as political.  It all made for a fine farewell spectacle, as principals and chorus (pictured above) sang with well-coordinated might and ardour. Yet this Masonic-style splendour meshed uneasily with the transfixing intimacy of Florestan and Leonore that it celebrated. Freedom and justice, once a personal mission, had become a public sacrament: a secular mass. This great affirmation lifts the heart but perhaps it swamps the still, small voice of dauntless truth – and love – at this work’s core.

It all made for a fine farewell spectacle, as principals and chorus (pictured above) sang with well-coordinated might and ardour. Yet this Masonic-style splendour meshed uneasily with the transfixing intimacy of Florestan and Leonore that it celebrated. Freedom and justice, once a personal mission, had become a public sacrament: a secular mass. This great affirmation lifts the heart but perhaps it swamps the still, small voice of dauntless truth – and love – at this work’s core.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Add comment