A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds | reviews, news & interviews

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Mind, body, body, mind. Medical science confirms the powerful two-way traffic between emotional and physical health.

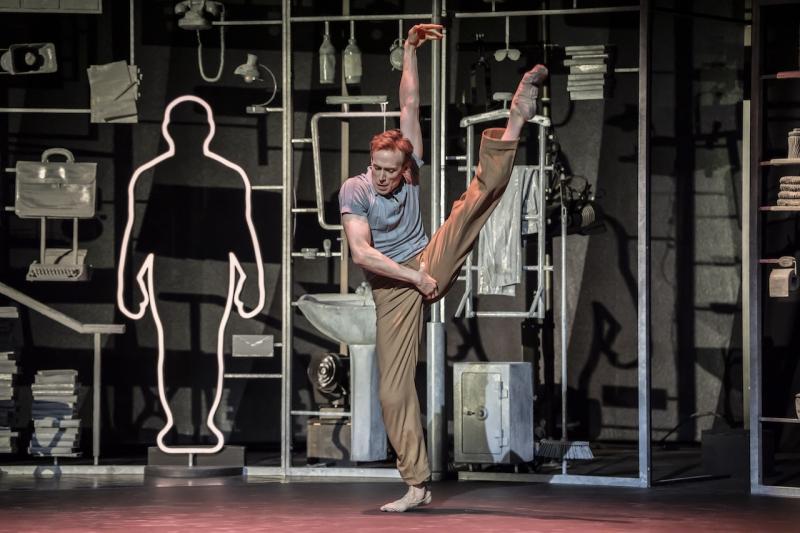

Stage left is a neon outline of a man, the kind of outline you might find on the door to the gents. Within it stands the actor-dancer Ed Watson (pictured top). It’s as if someone has asked him to stand still for a moment and drawn around him in thick white pen. Stage right is a much larger neon outline of a man’s head in profile. Framed by this head, on a raised platform, sits the singer-songwriter John Grant (pictured below), a bearish presence who will relay George’s thoughts to us in song for the next two hours, sometimes accompanying himself rather ploddingly on piano. Like all neat ideas this one flags rather quickly. Nothing is that clear-cut.

Isherwood’s original story, set in 1962, concerns the struggle of a middle-aged gay man, a university lecturer in southern California, to come to terms with the sudden death of his long-term partner, Jim. Given the general rejection of same sex love as warped and sinful, George feels unable to reveal his grief to any living person. Instead, he internalises it to a degree that is physically crippling, rendering him unable to face his students or even his friends. He finds fleeting solace only in imagined conversations with his late partner. It’s these all-in-the-mind encounters and flashbacks that paradoxically spur the choreographer Jonathan Watkins to his best work, finding super-fine nuance in the pair’s tender exchanges that belies the crude division of head versus beating heart.

Isherwood’s original story, set in 1962, concerns the struggle of a middle-aged gay man, a university lecturer in southern California, to come to terms with the sudden death of his long-term partner, Jim. Given the general rejection of same sex love as warped and sinful, George feels unable to reveal his grief to any living person. Instead, he internalises it to a degree that is physically crippling, rendering him unable to face his students or even his friends. He finds fleeting solace only in imagined conversations with his late partner. It’s these all-in-the-mind encounters and flashbacks that paradoxically spur the choreographer Jonathan Watkins to his best work, finding super-fine nuance in the pair’s tender exchanges that belies the crude division of head versus beating heart.

The cast is led by two of the most subtle actor-dancers of recent times, both now mature but on fine form (Ed Watson retired from the Royal Ballet four years ago, Jonathan Goddard is a seasoned freelancer). It remains a joy to see Watson extend one long and shapely leg up to his ear, a joy unalloyed by worry about what he might suffer for it afterwards. It’s also a pleasure to be reminded of Goddard’s possession of the most beautifully pointed feet in contemporary dance. Crucially, there is chemistry between the pair on stage, enough to blow the windows of the lab. We fully believe in their relationship, and the sun comes out whenever they exchange a smile. This is an unexpected bonus in a story about grief.

The less significant bits of the show can be harder to read. It’s not clear who or what are the figures in smudgy nude suits who shudder, writhe and wrestle with the unhappy George in an early scene. Later, the same ensemble posited as drivers in morning rush hour on a six-lane freeway is witty and precise. As is a lecture-room scene which offers clever dance metaphors for the students’ various responses to George’s teaching (pictured above). Kristen McNally (pictured above with Watson) is highly watchable as the female friend whose carelessly flirtatious manner tips him into a serious panic attack, and James Hay is a revelation as the student who finally breaks through George’s spiritual numbness by suggesting a skinny dip in the Atlantic.

The less significant bits of the show can be harder to read. It’s not clear who or what are the figures in smudgy nude suits who shudder, writhe and wrestle with the unhappy George in an early scene. Later, the same ensemble posited as drivers in morning rush hour on a six-lane freeway is witty and precise. As is a lecture-room scene which offers clever dance metaphors for the students’ various responses to George’s teaching (pictured above). Kristen McNally (pictured above with Watson) is highly watchable as the female friend whose carelessly flirtatious manner tips him into a serious panic attack, and James Hay is a revelation as the student who finally breaks through George’s spiritual numbness by suggesting a skinny dip in the Atlantic.

The Manchester Collective, playing behind a screen, steer the various moods of Jasmin Kent Rodgman’s score, jazz saxophone in the ascendant. The set (Chiara Stephenson) is a semicircular grey wall hung with the clutter of a shared domestic life. Here are so many objects that you keep spotting more through the dim light as the piece progresses, though I could have done without the spotlighting of items pertaining to each scene - sports equipment for a tennis match, a set of cocktail glasses when George gets drunk. All too obvious. Ditto screening the song lyrics as each line is delivered. This doubly backfires in that it draws attention to the frequent banality of the words, words which may have sat happily in Isherwood’s prose, but which don’t stand up as poetry. Just one or two lines are memorable. “Pain is a glacier moving through you …” prompts a fine choreographic response as Watson traces with his fingers imagined channels of pain from the top of his chest to his groin. There are many such resonant moments. A careful edit could make the viewer’s experience of A Single Man more consistent.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Add comment