RNCM International Diploma Artists, BBC Philharmonic, MediaCity, Salford review - spotting stars of tomorrow | reviews, news & interviews

RNCM International Diploma Artists, BBC Philharmonic, MediaCity, Salford review - spotting stars of tomorrow

RNCM International Diploma Artists, BBC Philharmonic, MediaCity, Salford review - spotting stars of tomorrow

Cream of the graduate crop from Manchester's Music College show what they can do

Two concerts in the BBC Philharmonic’s series in their own studio form the climax of studies at the Royal Northern College of Music for a small number of soloists on the postgraduate International Artist Diploma there, and also for some young conductors on the master’s course run by Mark Heron and Clark Rundell.

The conductors get the chance to direct the BBC Philharmonic and the soloists perform with them – it’s a chance to spot stars of tomorrow. The IAD represents, says the RNCM, the highest level of performance achievement there, welcoming a select group of exceptional artists each year who are poised to embark on international careers. This year the concerts at MediaCity in Salford saw three virtuosic soloists and four young conductors demonstrating what they could do – it was quite a showcase.

Findlay Spence (pictured right), already known as a member of the Fibonacci Quartet and as a solo cellist, performed Lutosławski’s Cello Concerto, written for Rostropovich and premiered by him in the UK in 1970. It’s not just extraordinarily virtuosic but demands much in terms of its musical language, stretching all the techniques of cello sound production in a long opening solo passage (and later) and requiring the ability to harness its considerable nervous energy and complex rhythms (for both soloist and orchestra) and also for the solo to soar in high cantabile style. In the final two movements Lutosławski cheerfully asks the orchestra to go freewheeling in aleatoric vein, and the work takes on the quality of a battle in its final section – which Spence assuredly won.

Findlay Spence (pictured right), already known as a member of the Fibonacci Quartet and as a solo cellist, performed Lutosławski’s Cello Concerto, written for Rostropovich and premiered by him in the UK in 1970. It’s not just extraordinarily virtuosic but demands much in terms of its musical language, stretching all the techniques of cello sound production in a long opening solo passage (and later) and requiring the ability to harness its considerable nervous energy and complex rhythms (for both soloist and orchestra) and also for the solo to soar in high cantabile style. In the final two movements Lutosławski cheerfully asks the orchestra to go freewheeling in aleatoric vein, and the work takes on the quality of a battle in its final section – which Spence assuredly won.

Conductor was Benjamin Voce (pictured right), who in addition to piloting the concerto safely through its complexities opened the concert with something much more mainstream and familiar – Johann Strauss’s overture to Die Fledermaus. Austrian orchestras play it liltingly, as if imbibed in their mothers’ milk, but its undulating patches of liveliness and sentiment can take more thoughtful treatment than mere tradition dictates. Voce varied the tempi as a sequence of step-changes, bringing weight and something near serenity to it in places; and, with the Philharmonic led by Yuri Torchinsky, whipped up the pace well before the end, leading to a furious finish and ferocious final bar.

Conductor was Benjamin Voce (pictured right), who in addition to piloting the concerto safely through its complexities opened the concert with something much more mainstream and familiar – Johann Strauss’s overture to Die Fledermaus. Austrian orchestras play it liltingly, as if imbibed in their mothers’ milk, but its undulating patches of liveliness and sentiment can take more thoughtful treatment than mere tradition dictates. Voce varied the tempi as a sequence of step-changes, bringing weight and something near serenity to it in places; and, with the Philharmonic led by Yuri Torchinsky, whipped up the pace well before the end, leading to a furious finish and ferocious final bar.

Alec Frank-Gemill (pictured left), who already has a successful career as French horn soloist, chamber musician and orchestra principal, next took on the role of conductor in the first concert. Schumann’s Manfred overture was his advertised task – a dramatic piece where traditional form is broken open to tell a Romantic story, and calling for careful attention to the notorious thickness of Schumann’s scoring. It had an admirably sharp and clean beginning and caught the required “passionate” idiom, the players warming to their conductor’s approach. An unadvertised extra piece followed – but an appropriate one in view of what was to come and the title of “Operatic Adventures” given to the concert – in the shape of Weber’s overture to Oberon. This was well-trodden territory for the Phil, of course (and the parts looked old enough to date from 1826) and under Alec Frank-Gemill’s baton the orchestra shone with tender feeling at the outset, glowed in the woodwind solos and concluded the piece with a neatly proportioned coda.

Alec Frank-Gemill (pictured left), who already has a successful career as French horn soloist, chamber musician and orchestra principal, next took on the role of conductor in the first concert. Schumann’s Manfred overture was his advertised task – a dramatic piece where traditional form is broken open to tell a Romantic story, and calling for careful attention to the notorious thickness of Schumann’s scoring. It had an admirably sharp and clean beginning and caught the required “passionate” idiom, the players warming to their conductor’s approach. An unadvertised extra piece followed – but an appropriate one in view of what was to come and the title of “Operatic Adventures” given to the concert – in the shape of Weber’s overture to Oberon. This was well-trodden territory for the Phil, of course (and the parts looked old enough to date from 1826) and under Alec Frank-Gemill’s baton the orchestra shone with tender feeling at the outset, glowed in the woodwind solos and concluded the piece with a neatly proportioned coda.

Weber’s music as transformed by Hindemith completed the programme of the first concert, the four substantial movements of the Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria Weber (in olden days a Barbirolli favourite for bringing a programme to an exhilarating close) entrusted to conductor Connor Lyster (pictured left). A percussionist by background (Iike Neeme Järvi), he has the gifts of economy of movement and focused contact with his musicians. The Allegro seemed to embody fun for them and us hearers, too; the mock-orientalist “Turandot” scherzo was jolly – almost in beer garden manner, but with clear articulation and a finely controlled crescendo. The Andantino proved mellow, charming and cleverly crafted in dynamics, and the concluding Marsch had a touch of swagger (though gently and subtly) and made its way to a fine and resonant climax.

Weber’s music as transformed by Hindemith completed the programme of the first concert, the four substantial movements of the Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria Weber (in olden days a Barbirolli favourite for bringing a programme to an exhilarating close) entrusted to conductor Connor Lyster (pictured left). A percussionist by background (Iike Neeme Järvi), he has the gifts of economy of movement and focused contact with his musicians. The Allegro seemed to embody fun for them and us hearers, too; the mock-orientalist “Turandot” scherzo was jolly – almost in beer garden manner, but with clear articulation and a finely controlled crescendo. The Andantino proved mellow, charming and cleverly crafted in dynamics, and the concluding Marsch had a touch of swagger (though gently and subtly) and made its way to a fine and resonant climax.

The second concert offered two soloists – piano and violin – and two conductors, each with something rather lighter than virtuoso concerto playing to make their own contribution to. The title was “Vibrant folk influences”, which fitted the bill in at least three cases.

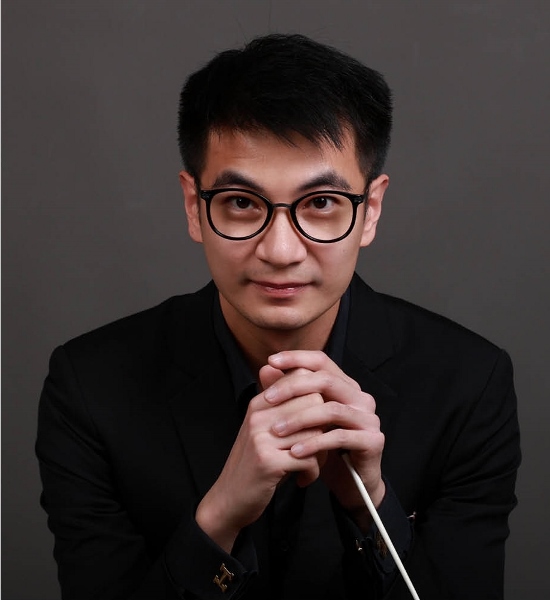

Conductor Harry Lai (pictured right) opened with Busoni’s Comedy Overture. Several composers have used that title for some kind of jeu d’esprit, though very few of them contain any genuine jokes (Hamilton Harty’s does have one, but Busoni’s is really more about high spirits). Lai had the Philharmonic (again led by Yuri Torchinsky) giving out an attractively light and airy sound, and kept the phrasing flowing. Sure-footed accelerations and decelerations, well controlled crescendos and an impressively rumbustious burst of counterpoint all contributed to the impact of the piece as a jolly romp. Harry Lai’s abilities were clearly obvious in his accompanying of Susanna Braun in Grażyna Bacewicz's Piano Concerto. It’s not a mainstream one today but they made a powerful case for its being one. Written in the Poland of 1949, it had to follow the prevailing Soviet-influenced orthodoxy of using traditional styles and structures and incorporating folk music if at all possible: the fact that it does this so effectively makes it a striking piece as well as a vehicle for pianistic virtuosity.

Conductor Harry Lai (pictured right) opened with Busoni’s Comedy Overture. Several composers have used that title for some kind of jeu d’esprit, though very few of them contain any genuine jokes (Hamilton Harty’s does have one, but Busoni’s is really more about high spirits). Lai had the Philharmonic (again led by Yuri Torchinsky) giving out an attractively light and airy sound, and kept the phrasing flowing. Sure-footed accelerations and decelerations, well controlled crescendos and an impressively rumbustious burst of counterpoint all contributed to the impact of the piece as a jolly romp. Harry Lai’s abilities were clearly obvious in his accompanying of Susanna Braun in Grażyna Bacewicz's Piano Concerto. It’s not a mainstream one today but they made a powerful case for its being one. Written in the Poland of 1949, it had to follow the prevailing Soviet-influenced orthodoxy of using traditional styles and structures and incorporating folk music if at all possible: the fact that it does this so effectively makes it a striking piece as well as a vehicle for pianistic virtuosity.

Susanna Braun (pictured left) had no problems with the display elements, but found warmth and guileless purity in the gentler writing: the first movement’s folk-derived and lyrical second theme, for instance, was thoughtfully articulated (after she gave careful pride of place to the orchestral wind solo that introduces it), and she caught a gentle, bitter-sweet and evocative quality in the slow movement, despite the thickly orchestrated writing that goes with it. The concerto has no cadenzas, but the first movement has a long solo passage, emerging here with ringing tone and flowing runs and figuration, shortly before the close, and the finale turns the piano at one point into a thunderous accompanist, in off-beat chords, for the orchestra: a role she filled exuberantly. Harry Lai attended in detail to the needs of the orchestra, such as the cellos’ pizzicati that follow one of the first movement solo episodes, and sustained the increase in tension that’s part of the finale’s rondo structure very effectively.

Susanna Braun (pictured left) had no problems with the display elements, but found warmth and guileless purity in the gentler writing: the first movement’s folk-derived and lyrical second theme, for instance, was thoughtfully articulated (after she gave careful pride of place to the orchestral wind solo that introduces it), and she caught a gentle, bitter-sweet and evocative quality in the slow movement, despite the thickly orchestrated writing that goes with it. The concerto has no cadenzas, but the first movement has a long solo passage, emerging here with ringing tone and flowing runs and figuration, shortly before the close, and the finale turns the piano at one point into a thunderous accompanist, in off-beat chords, for the orchestra: a role she filled exuberantly. Harry Lai attended in detail to the needs of the orchestra, such as the cellos’ pizzicati that follow one of the first movement solo episodes, and sustained the increase in tension that’s part of the finale’s rondo structure very effectively.

Felicity Cliffe (pictured right) was conductor for the Overture and Intermezzo from Ethel Smyth’s comic opera The Boatswain’s Mate. The overture is in reality more of a comic piece than Busoni’s, as she demonstrated, making its second subject wheel along with charm and excellent wind-strings balance. Even the March of the Women (Smyth’s contribution to the suffragiste cause) had a touch of ironic mock-solemnity to it that would fit precisely with the tongue-in-cheek woman-gets-one-over-on-a-man story in the little drama that follows (about a chap who thinks he’s God’s gift to a widowed pub landlady but gets his comeuppance from her with no mistake – it was given in a miniature version at last year’s Buxton Festival). The Intermezzo, opening with a solemn theme for horns which kept its steady underlying tread as it passed through the orchestra in long-drawn phrases, was likewise mock-tragic in effect, though ending with a note of charm on its final chord. There’s more to Ethel than the familiar picture of the campaigner conducting her supporters with a toothbrush suggests …

Felicity Cliffe (pictured right) was conductor for the Overture and Intermezzo from Ethel Smyth’s comic opera The Boatswain’s Mate. The overture is in reality more of a comic piece than Busoni’s, as she demonstrated, making its second subject wheel along with charm and excellent wind-strings balance. Even the March of the Women (Smyth’s contribution to the suffragiste cause) had a touch of ironic mock-solemnity to it that would fit precisely with the tongue-in-cheek woman-gets-one-over-on-a-man story in the little drama that follows (about a chap who thinks he’s God’s gift to a widowed pub landlady but gets his comeuppance from her with no mistake – it was given in a miniature version at last year’s Buxton Festival). The Intermezzo, opening with a solemn theme for horns which kept its steady underlying tread as it passed through the orchestra in long-drawn phrases, was likewise mock-tragic in effect, though ending with a note of charm on its final chord. There’s more to Ethel than the familiar picture of the campaigner conducting her supporters with a toothbrush suggests …

Krystof Kohout (pictured left) completed the feast of virtuosity as soloist (with Felicity Cliffe conducting) in Martinů’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra no. 1 – a piece that, though written in the 1930s for Samuel Dushkin, didn’t get its premiere until 1973. It’s one that’s rich with solo violin bravura almost from the first bar (the orchestra gets things going with a six-note theme, of which five are Es in different registers, and the violin has to take that as its starting point): double, triple and quadruple stops, arpeggios, harmonics – you name them, this has them. Krystof Kohout relished all of those, but the special quality of the piece lies in Martinů’s high-flying, gorgeous melodies (one of them in the style of a folk song), which he played with great beauty. There’s more folk-inspired song-like melody in the slow movement, in which the solo violin had its own deeply evocative moment, and the last movement brings a set of short cadenzas interwoven with orchestral contributions before gradually building towards its finish, with exceptional brilliance for the solo. Krystof Kohout was master of it all, and Felicity Cliffe handled its demands with unruffled skill – keeping rhythmic impetus where needed, synchronising solo and orchestra capably, and in calm control of the most impulsive moments of the finale.

Krystof Kohout (pictured left) completed the feast of virtuosity as soloist (with Felicity Cliffe conducting) in Martinů’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra no. 1 – a piece that, though written in the 1930s for Samuel Dushkin, didn’t get its premiere until 1973. It’s one that’s rich with solo violin bravura almost from the first bar (the orchestra gets things going with a six-note theme, of which five are Es in different registers, and the violin has to take that as its starting point): double, triple and quadruple stops, arpeggios, harmonics – you name them, this has them. Krystof Kohout relished all of those, but the special quality of the piece lies in Martinů’s high-flying, gorgeous melodies (one of them in the style of a folk song), which he played with great beauty. There’s more folk-inspired song-like melody in the slow movement, in which the solo violin had its own deeply evocative moment, and the last movement brings a set of short cadenzas interwoven with orchestral contributions before gradually building towards its finish, with exceptional brilliance for the solo. Krystof Kohout was master of it all, and Felicity Cliffe handled its demands with unruffled skill – keeping rhythmic impetus where needed, synchronising solo and orchestra capably, and in calm control of the most impulsive moments of the finale.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

Add comment