Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique, Ravel: La Valse Orchestre de Paris/Klaus Mäkelä (Decca)

Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique, Ravel: La Valse Orchestre de Paris/Klaus Mäkelä (Decca)

Rereading the composer’s memoirs and performing the Symphonie Fantastique have rekindled my interest in all things Berliozian, so this new album arrived at a good time. Bits of it are really impressive, Klaus Mäkelä audibly relishing some of Berlioz’s more outré effects. How could a 27 year-old from a non-musical background write something so radical? The first movement’s tonal shifts are brilliantly managed by Mäkelä – try the moment at 10’40” where the clouds suddenly descend, and note how he gives extra emphasis to the cello and bass lines as the music gradually picks up again. Berlioz’s waltz has the right lilt, though I wish the harps were more prominent in the mix, and the long "Scène aux champs" is expansive but hangs together beautifully. I’m less convinced by what follows: the playing of the Orchestre de Paris is terrific, but often feels too smooth and unruffled. Turn to, say, Charles Munch or Thomas Beecham in this work and the instrumental colours are more distinct, the edges rougher. I wanted louder trombone pedals in the “March au supplice”, though Mäkelä handles the actual decapitation brilliantly, the solo clarinet’s pleas for clemency brutally ignored. We hear some impressive bells in the finale but the music mostly simmers rather than boils. Instead, try Munch’s 1962 Boston Symphony version on RCA, his closing minutes a potent blend of terror and exhilaration.

The coupling is another danse macabre, Ravel’s crepuscular La Valse. Mäkelä seems to be heeding Ravel’s comments about the piece’s alleged subtext (“I did not envision a dance of death or a struggle between life and death.”), his witty reading accentuating the sleaziness, the decadence, before an unexpectedly brutal coda. A good rather than great album, then, though definitely the most satisfying disc Mäkelä has released with the Orchestre de Paris. Catch him at the Proms with the Concertgebouw Orchestra later this month, if you can find a ticket.

Bliss: Cello Concerto Guy Johnston (cello), Royal Liverpool Philharmonic/Andrew Manze (Onyx Classics)

Bliss: Cello Concerto Guy Johnston (cello), Royal Liverpool Philharmonic/Andrew Manze (Onyx Classics)

This release is the latest fruit of the Bliss anniversary this year (he died in 1975). The Cello Concerto is a late work, from 1970, part of the flurry of productivity in his last years. It was commissioned by Rostropovich, who premiered it at the Aldeburgh Festival, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Originally billed as a “concertino”, Britten persuaded the composer that it was actually a significant work and the title was duly upgraded.

This live recording is from a concert by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic in October 2024, with Guy Johnston taking the solo part. It’s a welcome addition to the piece’s discography – there a number of distinguished previous recordings, by Robert Cohen, Tim Hugh, Arto Noras and my hitherto favourite, Raphael Wallfisch with Vernon Handley and the Ulster Orchestra, on a disc paired with a very fine Colour Symphony. The heart of this current version is the poignant and poised “Larghetto”, set between the barely suppressed energy of the outer movements. This central panel is thoughtful and reflective, Romantic in inclination, but always kept moving by Andrew Manze. Likewise, Guy Johnston revels in the long melodic lines without becoming self-indulgent, not trying to invest it with too much weight.

In balance terms, the cello sits within the orchestral texture, as it naturally would in live performance, without the pushing forward of the soloist characteristic of studio concertos. But the orchestra is chamber sized and lightly scored, so there is plenty of room for the cello, and the sense of collegiality that emerges is one of the best things about the performance. It is perhaps less stormy than the Wallfisch, with Johnston playing up the wistfulness and nostalgia, an important element of a piece that must have seemed very old-fashioned in 1970. But all these years later it can just be enjoyed on its own terms, which is – if certainly not a par with the Elgar – alongside, say, the Walton and Finzi in the catalogue of British cello concertos. Bernard Hughes

Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 (finale revised by Dr John A. Phillips) Hallé/Kahchun Wong (Hallé)

Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 (finale revised by Dr John A. Phillips) Hallé/Kahchun Wong (Hallé)

Three-movement version Norrköping Symphony Orchestra/Karl-Heinz-Steffens (Orchid Classics

I’m still getting my head round the very existence of a ‘complete’ Bruckner 9th Symphony. The familiar three-movement edition still feels and sounds immutably ‘right’ to me. Simon Rattle’s 2012 Berlin Philharmonic recording made reconsider, his later live remake on the orchestra’s own label even more convincing. I’ll go with conductor Kahchun Wong’s assertion that we now have a choice between two different symphonies “where the same musical DNA unfolds in profoundly different ways, much like a multiverse of possibilities”. That we’re ultimately heading towards a positive outcome shouldn’t make the third movement “Adagio” any less emotional, and one of this live performance’s strengths is just how moving it is, Wong’s Hallé players magnificent in the scarier climaxes and wonderfully hushed in the final minutes. I listened to this team’s BBC Proms Mahler 2 on Radio 3 and was impressed by Wong’s ability to maintain tension at slow tempi; here, Bruckner’s first movement is on the expansive side but never sags. The scherzo is also on the expansive side but still moves, the grinding dissonances all the more powerful as a consequence.

The reconstructed finale began life in the early 1980s, a collaboration between four musicologists. One of them, Dr John A Phillips, worked alone on this latest revision and provides a cogent summary of the movement in the booklet note. It’s generally accepted that the movement was left complete in short score on Bruckner’s death but significant pages of manuscript were filched by fans and souvenir hunters. Phillips stresses that the vast majority of what we hear is authentic Bruckner, and that “at no point was any independent motivic material introduced, nor was it required.” Some moments are spine-tingling, especially the resplendent chorale at 5’23”, and the reintroduction of material heard earlier in the symphony is wholly characteristic. The D major ending is spectacular, though I think that the coda to Bruckner’s 8th Symphony is musically and emotionally more powerful. This release, edited together from live performances and rehearsals in Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall last year. And, as the only available version of this latest revision, it’s a keeper.

A new recording of the familiar three-movement score landed on my doormat at the same time as Wong’s, Katy Hamilton’s useful booklet essay sidestepping the question of the finale other than mentioning that Bruckner “seems to have made quite considerable progress” with it. I’d not hitherto tagged Karl-Heinz Steffens and the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra as purveyors of quality Bruckner, but this is an unexpectedly superb performance. Steffens was the Berlin Philharmonic’s principal clarinettist between 2001 and 2007 which probably accounts for the impressive wind and brass playing on show.

A new recording of the familiar three-movement score landed on my doormat at the same time as Wong’s, Katy Hamilton’s useful booklet essay sidestepping the question of the finale other than mentioning that Bruckner “seems to have made quite considerable progress” with it. I’d not hitherto tagged Karl-Heinz Steffens and the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra as purveyors of quality Bruckner, but this is an unexpectedly superb performance. Steffens was the Berlin Philharmonic’s principal clarinettist between 2001 and 2007 which probably accounts for the impressive wind and brass playing on show.

Try the perfectly attuned unison Ds at the symphony’s opening or the ecstatic trumpet fanfares two minutes into the “Adagio”, as impressive as any I’ve heard on disc, followed by an immaculately blended Wagner tuba chorale. Bruckner’s dissonant climaxes are genuinely terrifying here (sample the first movement’s doomy coda) and the scherzo has plenty of bite. Steffens relaxes nicely into the whimsical trio and the Norrköping strings have plenty of body in the slow movement. This is really, really good, and wonderfully recorded to boot: in a three-movement Bruckner 9 multiverse, this disc would be a top recommendation.

Paul Honey and Gregory Warren Wilson: Between Midnight and Sunrise (Quartz)

Paul Honey and Gregory Warren Wilson: Between Midnight and Sunrise (Quartz)

The first work on this album was meant to have been taped back in 2020. No prizes for guessing what prevented this. Composer Paul Honey planned to record his settings of poetry by Gregory Warren Wilson for his own satisfaction alone, but hearing the music for the first time when sessions began in March 2022 convinced him to compose and record a full album’s worth. Recast with solo cello instead of violin, Earth’s Imagined Corners sets four haiku. Cellist Justin Pearson’s opening soliloquy gives no hint as to what’s coming, the imperceptible entry of Jonathan Darbourne’s Locrian singers on a quiet sustained D a magical moment. “Leatherback”, the second in the sequence, depicts newly hatched turtles heading towards the sea, and “Fireflies” glows.

This album features a starry cast: soprano Grace Davidson duets with harpist Jean Kelly in “Spring’s First Migration” and “San Clemente at Dawn”, both exquisite, and tenor James Gilchrist is accompanied by pianist Anna Tilbrook in the song cycle A Wing of Light. It’s refreshing to hear contemporary art songs which are so readily accessible, the assorted vocal soloists singing as if they’re tackling repertoire standards. Try “Between Midnight and Sunrise”, baritone Johnny Herford and pianist Matthew Fletcher pondering the mysteries of the night (“the birds will print their fossicking in code/but I am still possessed by what I do not know.”) in style. It’s a gorgeous song. Try the five numbers which make up Dancing Alone, Herford really nailing the quickfire delivery needed in “Sitting out the Tarantella” – his delivery of the couplet “they stare back at me so placidly/I can almost smell their sobriety” is an album highlight, as is Honey accompanying mezzo-soprano Frances Gregory in “Any Other Way”. This is an appealing anthology from a composer I’d not encountered before, and it’s nicely engineered. Full texts are provided, though Quartz miss a trick in not giving us details of who’s singing and accompanying what.

Brooklyn Rider: The Four Elements (In A Circle Records)

Brooklyn Rider: The Four Elements (In A Circle Records)

Lots of fours here: four musicians in a string quartet, four works written during the last 100 years and four newly commissioned ones, Brooklyn Rider’s new album grouping the pieces into four groups matching Earth, Air, Fire and Water. You can even buy it as a four LP box set. I’ll admit to dipping in and out at first rather than listening to each element separately and liked what I heard very much – this is another superbly played anthology from an enterprising ensemble. Shostakovich’s 8th Quartet is placed, aptly, in the Fire segment, composed after a 1960 visit to Dresden to score a film depicting the city’s firebombing by Allied forces. Some performances overdo the sound and fury of the work. This one doesn’t, lyrical passages like the cello’s singing of the aria “Seryozha, my love” from Lady Macbeth, deeply moving. The Shostakovich is partnered with Californian composer Akshaya Tucker’s 2022 Hollow Flame, a visceral reaction to the effect of climate change on her home state. Air includes Dutilleux’s Ainsi la nui, its various technical effects brilliantly realised, plus Aere senza stelle (2022) by Portuguese composer Andreia Pinto Correia. Inspired by her memories of dust storms she experienced as a child, it concludes with a magical evocation of the Saharan wind “carrying an infinite stream of particles from the desert to other parts of the world”.

Colin Jacobsen’s A Short While To Be Here… (2023) opens Earth. Based on five folksongs first collected by Ruth Crawford, it’s a delight, not a million miles away from Bartok’s folksong transcriptions. It’s paired with Under My Feet & Up There, composed by Dan Trueman in 2023, a celebration of the subterranean, including roots, cicadas and tectonic plates. Water comes last, Conrad Tao’s 2023 rippling Undone suggested by the legend of water nymph Undine, imagining how she’d cope in an age of rising sea levels, “her waves higher and more dangerous than ever before” as a result of human intervention. And Osvaldo Golijov’s Tenebrae (2003) was first suggested by a trip to a planetarium and the sight of Earth as “a beautiful blue dot”, the music growing darker as we hone in and notice the problematic details, as if reading the small print. The textures are unfeasibly rich at some points; it’s difficult to believe that we’re hearing a quartet rather than a string orchestra.

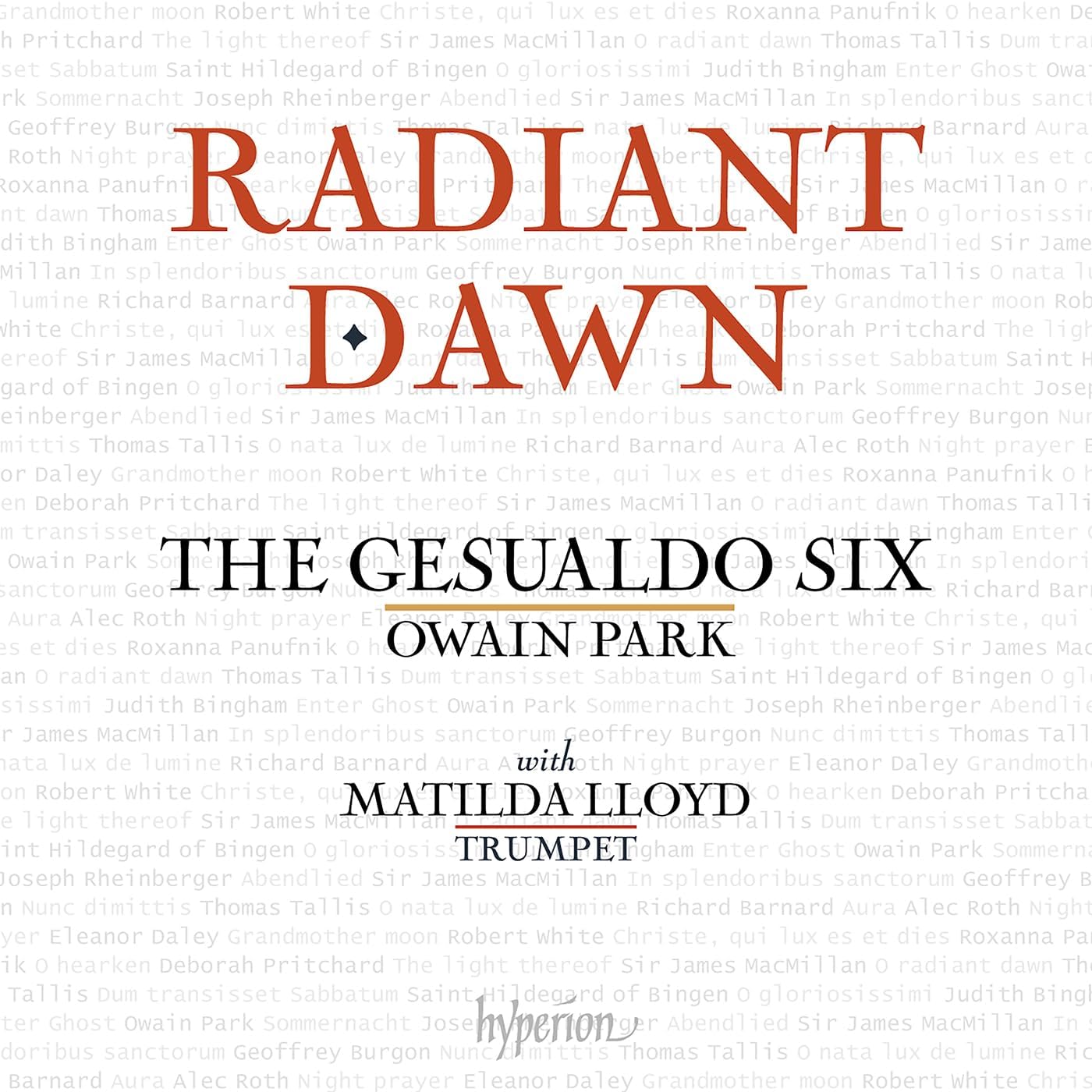

Radiant Dawn The Gesualdo Six/Owain Park, with Matilda Lloyd (trumpet) (Hyperion)

Radiant Dawn The Gesualdo Six/Owain Park, with Matilda Lloyd (trumpet) (Hyperion)

The 10th album on Hyperion by the prolific Gesualdo Six adds Matilda Lloyd’s trumpet to the usual mix, in pieces exploring changing light through the course of the day. The programme is put together with typical care, using Renaissance classics, newly composed pieces and the subtle inclusion of the trumpet to make a musical sequence that is more than a sum-of-parts. That said, I must confess I started at the end, with Geoffrey Burgon’s Nunc Dimittis, written to be the end-of-episode music for the legendary 1979 BBC TV adaptation of John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. There it is heard as a boy treble solo with strings and trumpet; here the string chords are taken by the singers and the solo by tenor Josh Cooter. His is a humble and unhurried reading, with Lloyd’s answering phrases equally spacious – making demands of breath control from the ensemble, who provide a warm harmonic bed. It’s exquisite.

Back to the beginning. Alex Roth’s Night Prayer has a blurred effect from English and Latin musical lines running alongside each other at different speeds, the trumpet observing from a distance. The title track is James MacMillan’s O Radiant Dawn and we also hear the piece it was inspired by/borrows from, Tallis’s O Nata Lux. Tallis’s piquant false-relations are bolder than anything in the MacMillan, although he perhaps offers more drama in his pleading upwards-reaching suspensions. Deborah Pritchard’s The light thereof is elegiac in tone, the trumpet understated – on this album we don’t hear its customary triumphal, military aspect, but the plangent, plaintive terrain the instrument can also inhabit.

Roxanna Panufnik’s O hearken is something marvellous, the opening building delicious cluster harmonies which sound like more than six voices, while the middle section has rising ribbons of scales intertwining to depict incense smoke “rising and mingling in the church rafters”. Of other contemporary pieces, Richard Barnard’s Aura has the trumpet act as bridge between two groups of three singers: both composer and ensemble demonstrate great control of shaping and building, the ebb and flow engrossing. Judith Bingham’s Enter Ghost is a showpiece for Matilda Lloyd, who plays athletic phrases around Josh Cooter reciting lines from Hamlet, while Park’s own Sommernacht, a response to a Max Reger song, has a dreamy summery listlessness. As ever with the Gesualdo Six the singing is unimpeachable, and on this album perfectly in sync with the brilliant programming. Bernard Hughes

Sky of My Heart New York Polyphony, LeStrange Viols (BIS)

Sky of My Heart New York Polyphony, LeStrange Viols (BIS)

This album by the extremely polished vocal quartet New York Polyphony is back weighted, with the best stuff coming towards the end. It combines some of the group’s standard repertoire – Byrd and Gibbons – with pieces by seven contemporary composers. Most of these are in an old/new musical language that makes the album cohere, but it’s not till LeStrange Viols join for three tracks at the end that it takes flight.

The biggest single piece – and my favourite – is Nico Muhly’s My Days, whose text combines Psalm 39 (which Gibbons himself set) with a written account of Gibbons’s own autopsy. It’s a moving piece, the vocalists belying their name by singing mainly homophonically, hymnic phrases that are commented on by the viols, their astringent harmony and metallic sound hitting a poignant emotional note. The music has a Gibbons-like verse structure and a hieratic quality that I found very affecting. Immediately followed by actual Gibbons – The Silver Swan, accompanied by viols – and preceded by Andrew Smith’s Katarsis, it makes for a powerful final sequence. Katarsis, a memorial to Smith’s father, who died in Covid times, is bleak and restrained, the quartet often reduced to two voices, not an ounce of excess flesh on the bones.

Also with a mournful tread is Ivan Moody’s setting of the Song of Songs, channelling the music of the medieval with no overt nods towards the lavish eroticism of the text: the music is still and detached. But I much preferred it to Becky McGlade’s Of the Father’s Love Begotten, a harmonic hodge-podge that starts with a churchy chant but swerves uncomfortably into chromatic lushness and a kind of anchorless barbershop. Akemi Naito’s Tsuki no Waka is more convincing, again with the singers effacing themselves, their singing quiet and held-back. Paul Moravec’s two Whitman settings at last injected a bit of forward momentum into proceedings and his vocal settings have that brilliant effect of making four voices sound like more. This quality is shared by Byrd in his Mass for Four Voices, here performed with the viols doubling the vocal parts. In fact, I would have liked more viols throughout, and perhaps a bit more Gibbons instead of Tavener’s The Lamb, which I have never been able to like. Bernard Hughes

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Ivan Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Ivan Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

BBC Proms: Batsashvili, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Ryan Wigglesworth review - grief and glory

Subdued Mozart yields to blazing Bruckner

BBC Proms: Batsashvili, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Ryan Wigglesworth review - grief and glory

Subdued Mozart yields to blazing Bruckner

Classical CDs: Hens, Hamburg and handmaids

An unsung French conductor boxed up, plus Argentinian string quartets and baroque keyboard music

Classical CDs: Hens, Hamburg and handmaids

An unsung French conductor boxed up, plus Argentinian string quartets and baroque keyboard music

BBC Proms: McCarthy, Bournemouth SO, Wigglesworth review - spring-heeled variety

A Ravel concerto and a Walton symphony with depth but huge entertainment value

BBC Proms: McCarthy, Bournemouth SO, Wigglesworth review - spring-heeled variety

A Ravel concerto and a Walton symphony with depth but huge entertainment value

BBC Proms: First Night, Batiashvili, BBCSO, Oramo review - glorious Vaughan Williams

Spirited festival opener is crowned with little-heard choral epic

BBC Proms: First Night, Batiashvili, BBCSO, Oramo review - glorious Vaughan Williams

Spirited festival opener is crowned with little-heard choral epic

Add comment