Hespèrion XXI, Savall, QEH review - an evening filled with laughter and light | reviews, news & interviews

Hespèrion XXI, Savall, QEH review - an evening filled with laughter and light

Hespèrion XXI, Savall, QEH review - an evening filled with laughter and light

An exhilarating exploration of innovation in 16th and 17th century repertoire

For the first encore of the evening, it was not just the audience but the whole ensemble of Hespèrion XXI that was mesmerised as its leader, Jordi Savall, executed a fiendishly rapid sequence of notes that sent the rosin from his bow rising up like smoke.

This joyful, sharply inventive concert with his group was titled Baroque Revolution, reflecting the innovative spirit of the 16th and 17th century composers it featured from Europe and South America. The programme began with an elegant amuse bouche from Vincenzo Ruffo, an Italian priest and choirmaster who experimented with different forms of music and notation.

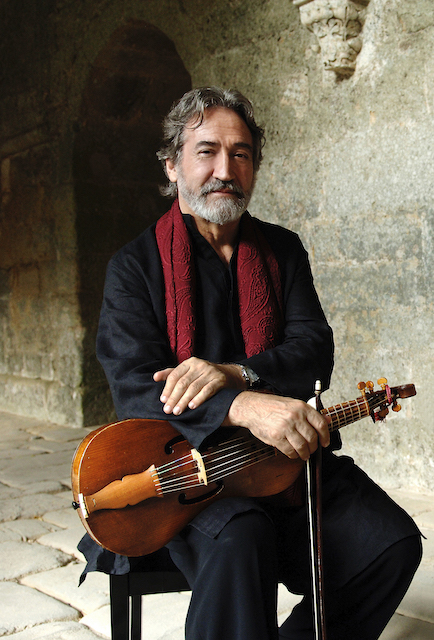

When Savall (pictured below by David Ignaszewski) walked on with the other members of Hespèrion XXI, he was leaning on a crutch, but the moment he started playing his treble viol he seemed physically liberated. Ruffo – according to the programme – was the first composer to write capricci (pieces of fast, playful, often virtuosic music), and here we heard the range of what such music could express in "La gamba", "La disperata" and "La piva" from Capricci in musica a tre voci.

The first movement was filled with light and élan as Savall duetted with Xavier Puertas on the violone [ancestor of the double bass], accompanied by the patter of David Mayoral on the tambourine. "La disperata" (The desperate) was – appropriately for its name, full of yearning and lamentation, its harmonies as pungently bitter as rosemary. Then "La piva" – inspired by peasant dances accompanied by bagpipes – took us into a more joyful realm again, with Andrew Lawrence-King on the arpa doppia (an Italian double-strung harp])introducing a sense of translucence and sunlight.

Next we were swept into the Sinfonia from Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima et di Corpo – the first drama set entirely to music. This stately work introduced new textures into the programme as it was led by the arpa doppia and Xavier Diaz-Latorre on the theorbo. The stateliness faded away and a sense of effervescence prevailed as the Sinfonia was succeeded by Cavalieri’s "Ballo del Granduca" from La Pellegrina. Diaz-Latorre replaced his theorbo with a more jaunty guitar, while the sense of vitality was heightened by vigorous dotted rhythms from the arpa doppia and the tambourine.

Next we were swept into the Sinfonia from Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima et di Corpo – the first drama set entirely to music. This stately work introduced new textures into the programme as it was led by the arpa doppia and Xavier Diaz-Latorre on the theorbo. The stateliness faded away and a sense of effervescence prevailed as the Sinfonia was succeeded by Cavalieri’s "Ballo del Granduca" from La Pellegrina. Diaz-Latorre replaced his theorbo with a more jaunty guitar, while the sense of vitality was heightened by vigorous dotted rhythms from the arpa doppia and the tambourine.

Tobias Hume was a soldier/composer inclined to pranks: one of his compositions demanded that two players perform on the same viol, with the smaller player sitting on the lap of the larger. Happily – or sadly according to your perspective – that did not feature in the programme: instead we had the stunningly beautiful The Lady Cane’s delight – almaine, which brought a mournful, lyrical tone to proceedings, before the exhilarating complexity of the interweaving runs in Orlando Gibbons’ Fantasia a three, no 12. Following this the little-known Variations on a ground (1610, Anonymous) began like exquisite embroidery in sound. This evolved into an energising cascade of notes from Savall which swiftly became a jaw-dropping display of technical fireworks.

Overall the programme featured 18 items, plus two encores, so there’s no room in this review to analyse each element. One unifying aspect of this delightfully disparate evening was the joy of observing the relationship between the players, which felt more akin to the dynamics of a jazz band than a classical ensemble. As the percussionist, Puertas was given particularly free rein, not least in William Brade’s lilting Scottish Dance, where his boisterous introduction of the “boing boing boings” of a Jewish harp added a distinctive comedy to proceedings. Later, Kapsberger’s Variations sur La Folia was a gorgeous demonstration of theorbo player Diaz-Latorre’s virtuosity.

Yet while it was very much an ensemble, it was also indisputably Savall’s evening – not because of any sense of ego, but because of the uncompromising intensity of his relationship with the music. A particularly special moment was when he told the audience, in slightly halting English, that he had made his debut in the Queen Elizabeth Hall 54 years ago. The audience's whoops and applause were testament to everything he has achieved more than half a century later. Playing on the treble viol throughout the concert, he took us through emotions that ranged from the velvety grief of the opening of Biagio Marini’s Passacaglia a four, Op. 22 to the dizzying ecstasy of the Anonymous Folias criollas.

Yet while it was very much an ensemble, it was also indisputably Savall’s evening – not because of any sense of ego, but because of the uncompromising intensity of his relationship with the music. A particularly special moment was when he told the audience, in slightly halting English, that he had made his debut in the Queen Elizabeth Hall 54 years ago. The audience's whoops and applause were testament to everything he has achieved more than half a century later. Playing on the treble viol throughout the concert, he took us through emotions that ranged from the velvety grief of the opening of Biagio Marini’s Passacaglia a four, Op. 22 to the dizzying ecstasy of the Anonymous Folias criollas.

For the second encore he even managed to imitate a – slightly eccentric – canary on his viol, with the ensemble members watching him in amused disbelief before they happily joined in. It was a testament as much to their enduring love and respect for him as for their impressive versatility, and a suitably teasing end to an evening full of laughter and light.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

Add comment