Classical CDs: Cannons, culverts and mooching cattle | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs: Cannons, culverts and mooching cattle

Classical CDs: Cannons, culverts and mooching cattle

Box sets celebrating a pair of conductors, plus baroque vocal music and a beguiling bassoon anthology

Antal Doráti in London: The Mercury Masters Vol. 1 (Decca Eloquence)

Antal Doráti in London: The Mercury Masters Vol. 1 (Decca Eloquence)

A couple of recent YouTube videos show DG engineers hard at work remastering Karajan’s 1970s Bruckner and Mahler recordings for new vinyl LP pressings. The process looks tortuous, the multitracked master tapes painstakingly examined and reassembled, artificial reverb added using an empty stairwell. Listen, say, to Karajan’s Berlin performances of Mahler 6 and Bruckner 8 and you’re struck by the density of sound, the orchestral sonority almost oppressive in loud tuttis. Yes, the playing is accomplished, but there’s a distinct lack of air, of light and shade. If only the Berliners could have decamped from the Philharmonie to Watford Town Hall to work with Mercury Living Presence, that label preferring to use just three strategically placed microphones in a sympathetic acoustic. Recording levels were not to be altered, bass and treble frequences unboosted, the Mercury approach to orchestral recording being to leave questions of balance to the conductor.

Conductor Antal Doráti began making LPs for Mercury with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in the early 1950s, those recordings already collated in a pair of Decca Eloquence box sets. This new 29-CD release is one of two celebrating his work in London, Volume 1 focussing exclusively on his work with the London Symphony Orchestra. Which, back in the mid-1950s, was perceived very much as an inferior ensemble to the Philharmonia and Royal Philharmonic, a self-governing group which took on any work offered to it, the playing standards erratic. Not that you’d notice when listening to Doráti’s first Mercury recordings with the orchestra, three 1956 albums containing music by Mozart, Rimsky-Korsakov and Mendelssohn superbly performed, captured in vivid stereo sound. Doráti never held a permanent position with the LSO but was a regular collaborator until the mid-1960s, his exacting standards undoubtedly a factor in the orchestra’s growing status (“the period of our close collaboration coincided with the orchestra’s rise to the top international rank”. Recording sessions could be tense affairs, horn-player (and soon-to-be orchestral chairman) Barry Tuckwell recalling the early years as “a boot camp… but the hard work was good for us”. Mercury liked working in London, the city offering relatively inexpensive and hard-working orchestras plus a selection of decent recording venues.

Conductor Antal Doráti began making LPs for Mercury with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in the early 1950s, those recordings already collated in a pair of Decca Eloquence box sets. This new 29-CD release is one of two celebrating his work in London, Volume 1 focussing exclusively on his work with the London Symphony Orchestra. Which, back in the mid-1950s, was perceived very much as an inferior ensemble to the Philharmonia and Royal Philharmonic, a self-governing group which took on any work offered to it, the playing standards erratic. Not that you’d notice when listening to Doráti’s first Mercury recordings with the orchestra, three 1956 albums containing music by Mozart, Rimsky-Korsakov and Mendelssohn superbly performed, captured in vivid stereo sound. Doráti never held a permanent position with the LSO but was a regular collaborator until the mid-1960s, his exacting standards undoubtedly a factor in the orchestra’s growing status (“the period of our close collaboration coincided with the orchestra’s rise to the top international rank”. Recording sessions could be tense affairs, horn-player (and soon-to-be orchestral chairman) Barry Tuckwell recalling the early years as “a boot camp… but the hard work was good for us”. Mercury liked working in London, the city offering relatively inexpensive and hard-working orchestras plus a selection of decent recording venues.

Doráti’s versatility was one of his calling cards, this set containing excellent performances of works by Handel, Haydn, Mendelssohn and Brahms alongside spikier 20th century repertoire. A 1959 performance of Dvořák’s Symphony 8 glows, the finale’s coda one of the brassiest on disc. And try the second movement of Mendelssohn’s ‘Scottish’ Symphony, the wind and string articulation ideally clear. Brahms 1 boasts an imposing Barry Tuckwell horn solo, the player equally impressive in Doráti’s Tchaikovsky 5th. There’s a decent mono version of The Nutcracker in one of the Minneapolis boxes, but the stereo LSO version is better played and recorded, here squeezed onto a single disc.

Doráti’s versatility was one of his calling cards, this set containing excellent performances of works by Handel, Haydn, Mendelssohn and Brahms alongside spikier 20th century repertoire. A 1959 performance of Dvořák’s Symphony 8 glows, the finale’s coda one of the brassiest on disc. And try the second movement of Mendelssohn’s ‘Scottish’ Symphony, the wind and string articulation ideally clear. Brahms 1 boasts an imposing Barry Tuckwell horn solo, the player equally impressive in Doráti’s Tchaikovsky 5th. There’s a decent mono version of The Nutcracker in one of the Minneapolis boxes, but the stereo LSO version is better played and recorded, here squeezed onto a single disc.

A 1957 Prokofiev LP belies its age, Doráti’s hair-raising Scythian Suite something to enjoy at full volume when the neighbours are out. Sample the horns and low brass at the start of “The Enemy of God and the Dance of the Spirits”, or the ear-splitting sunrise that closes the work. Rimsky-Korsakov’s suite from Le Coq d’Or is superbly done, as is a selection from Khachaturian’s cheesy-but-fun ballet Gayaneh, the “Sabre Dance” wonderfully vulgar. Best of all is a famous account of Stravinsky’s complete Firebird, full of ear-catching detail and wonderfully recorded. Plus Byron Janis playing Rachmaninov’s 3rd Piano Concerto. He’s fantastic, and Doráti’s LSO accompany brilliantly.

I grew up with Doráti’s 1980s Detroit Symphony recording of Copland’s Appalachian Spring; his 1961 LSO version isn’t quite as polished but holds up well. This version of the complete Billy the Kid ballet score is a triumph, with a spectacular gunfight and very rattly saloon bar piano. These scores can’t have been standard repertoire for UK orchestras in the 1960s, but the LSO musicians relish Copland’s tricky rhythms.

Other treats include the two Enescu Romanian Rhapsodies, Henryk Szeryng playing the Brahms Violin Concerto plus János Starker playing Dvorák. Two discs of Wagner extracts sit nicely alongside some Verdi operatic preludes and a trailblazing LP of Berg’s Lulu Suite and excerpts from Wozzeck, with soprano Helga Pilarczyk. And audiophiles will want to hear a recording of Beethoven’s schlocky Wellington’s Victory, overdubbed with vintage cannons from the West Point Military Academy. Presentation and documentation are excellent, the booklet stuffed with interesting information about Mercury’s technical approach, each disc with its original sleeve art. Spend a few days exploring this box and you’ll be tempted to start saving up for Volume 2.

Lovro von Matačić conducts the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra (Supraphon)

Lovro von Matačić conducts the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra (Supraphon)

Hungarian-born Antal Doráti left Europe in the early 1940s, becoming a US citizen in 1943. Croatian conductor Lovro von Matačić (1899-1985) wasn’t so lucky. His European career was thriving before World War 2 and he was appointed director of the Belgrade Opera in 1938. During occupation, Matačić was forcibly conscripted but continued to conduct until the fall of Nazism, the incoming Titoist regime regarding him with suspicion, at one point sentencing him to death. Eventually Matačić was pardoned, his international career restarting after being granted a passport in 1954. He stood in for Karajan in an EMI recording of Strauss’s opera Arabella and made guest appearances in Vienna and in Bayreuth. This six-CD box contains the recordings Matačić made with the Czech Philharmonic on the Supraphon label between 1959 and 1980, and they’re consistently impressive.

I’ve still got a vinyl copy of Matačić’s 1960 Tchaikovsky 5th Symphony, which I can remember fitting on one side of a C90 cassette with a few minutes to spare. The performance is as good as I remember it being, one surprise being a swift, punchy first movement coda and a terrifying motto theme appearance in Tchaikovsky’s slow movement. Not even Matačić can tame the finale’s sprawl, but it hangs together pretty well and the final bars are electrifying. Tchaikovsky’s 6th was recorded eight years later, another exciting, unsung reading with an electrifying first movement development and a very stoic “Andante lamentoso”.

I’ve still got a vinyl copy of Matačić’s 1960 Tchaikovsky 5th Symphony, which I can remember fitting on one side of a C90 cassette with a few minutes to spare. The performance is as good as I remember it being, one surprise being a swift, punchy first movement coda and a terrifying motto theme appearance in Tchaikovsky’s slow movement. Not even Matačić can tame the finale’s sprawl, but it hangs together pretty well and the final bars are electrifying. Tchaikovsky’s 6th was recorded eight years later, another exciting, unsung reading with an electrifying first movement development and a very stoic “Andante lamentoso”.

The earliest recording here is a 1959 account of Beethoven’s Eroica. It’s a find, weighty and well-upholstered but with a thrilling sense of purpose. Cellos and basses dig deep in the funeral march and the scherzo dances. The same disc includes Matačić’s nifty two-movement suite from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, ideal if you’ve only got 25 minutes to spare instead of five hours. Another novelty item is Oldřich Korte’s The Story of The Flutes, an intriguing, 19-minute ‘symphonic drama’. Supraphon’s website describes this 1951 work as “one of the most significant and successful Czech symphonic compositions of the second half of the 20th century”. High praise indeed. It’s an attractive piece, beautifully played here.

The earliest recording here is a 1959 account of Beethoven’s Eroica. It’s a find, weighty and well-upholstered but with a thrilling sense of purpose. Cellos and basses dig deep in the funeral march and the scherzo dances. The same disc includes Matačić’s nifty two-movement suite from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, ideal if you’ve only got 25 minutes to spare instead of five hours. Another novelty item is Oldřich Korte’s The Story of The Flutes, an intriguing, 19-minute ‘symphonic drama’. Supraphon’s website describes this 1951 work as “one of the most significant and successful Czech symphonic compositions of the second half of the 20th century”. High praise indeed. It’s an attractive piece, beautifully played here.

The other three discs contain Bruckner symphonies, a Matačić speciality. His 1970 Bruckner 5 uses an unfamilar edition (uncredited) with cuts and some retouching, but it’s brashly enjoyable. More mainstream is a sublime account of Symphony No. 7 with some magnificent brass playing: the slow movement’s final minutes are sublime. Tempi are well-judged and there’s a beguiling lightness and wit in the finale. Symphony No. 9 is a live performance, spontaneous-sounding and emotionally gripping , entirely in keeping with a pertinent Matačić quote, the conductor telling Oldřich Korte that when conducting Bruckner “you have to leave your intellect at home and leave your heart wide open”. A fabulous box set, beautifully presented and annotated.

Helen Charlston: If the Fates allow - music by Henry and Daniel Purcell, John Eccles Helen Charlston (mezzo-soprano), Sounds Baroque (BIS)

Helen Charlston: If the Fates allow - music by Henry and Daniel Purcell, John Eccles Helen Charlston (mezzo-soprano), Sounds Baroque (BIS)

Helen Charlston’s deep affinity for and understanding of Purcell shines through gloriously on her debut on the BIS label. “Purcell’s music has become an innate part of me as a singer,” she notes. The recording was made in 2022 after an invitation to perform at the London Festival of Baroque Music, and when, as she says, “a lot of Purcell’s music was still on my performance wish list.” That’s unduly modest. This is a carefully planned and well-contrasted programme of intelligent and nuanced singing with musicality, variety, always balancing joy and pathos. Everything here is done with unassailable quality and assuredness.

We find, for example, completely exquisite, beautifully paced renditions of popular numbers. For anyone constructing a mixtape, “I attempt from love’s sickness” is just under two minutes of utterly concentrated bliss. And there is much more. Dramatic heft and variety and the ratcheting up of tension are there in “Tell me, some pitying angel…” Or we are suddenly needle-dropped into the plangent sighing and astonishing melisma of “The Cares of Lovers”. Or treated to the contrast of a florid vocal line with a soulful refrain from a bass viol (the superb Jonathan Manson) in “What a Sad Fate is Mine”.

And if keeping the whole album brimming with life, wasn’t enough, the liner note interview is an unexpected and brilliant deconstruction of the all-too-familiar artist interview. Charlston swaps roles and becomes the interviewer, with the great Emma Kirkby as her subject. Like everything else here, there is a good reason why this choice has been made. Charlston expresses her respect and gratitude to Emma Kirkby thus: “It’s because of you I feel a certain freedom and flexibility with which to approach Purcell’s music.” The conversation between the two of them goes deep into this music and its context. Talking about a particular melismatic episode, Charlston says, thoughtfully, and as an invitation to close and detailed listening: “The melisma is not really the distance between the notes: it’s the expression of how you get from one note to the other.” I seriously can’t imagine any listener anywhere being disappointed by this: a superb album which must surely be a shoo-in for end of the year ‘best-of’ lists. Sebastian Scotney

Misha Mullov-Abbado: Effra (Ubuntu Music)

Misha Mullov-Abbado: Effra (Ubuntu Music)

Start googling London’s minor rivers and you’ll disappear down a very deep rabbit hole. I’m familiar with the Fleet, the Ravensbourne and the splendidly named Quaggy, but the River Effra was new to me. Flowing into the Thames near Vauxhall, much of the Effra was channelled into a culvert and combined with a sewer by Joseph Bazalgette, its path through the south London hinterlands largely obscured. The river’s name is an apt title for Brixton resident and double bassist Misha Mullov-Abbado’s eclectic new album, a celebration of Brixton’s diversity, recorded with his regular sextet. “Traintracker” is an upbeat opener, Mullov-Abbado spinning nine exuberant minutes from a single repeated chord pattern, each player getting a moment in the spotlight. Drummer Scott Chapman’s solo, just before the six-minute mark, is a highlight. “Bridge” and “Rose” are dedicated to Mullov-Abbado’s wife, the latter’s nine minutes unfolding over a repeated E flat on piano.

“The Effra Parade” recalls an aimless lockdown urban walk, a number recently covered by the Neoteric Ensemble. “Canção De Sobriedade” is another Covid-era piece, its title alluding to the perils of unchecked alcohol consumption during the early stages of the pandemic. “Subsonic Glow” is punchy and positive, and album closer “Nanban” ends in a brilliant blaze of colour. Do catch Mullov-Abbado live: his sextet play in Oxford on 11th June, with dates in Stapleford, Swanage and Dorking in coming months, with full details on his website.

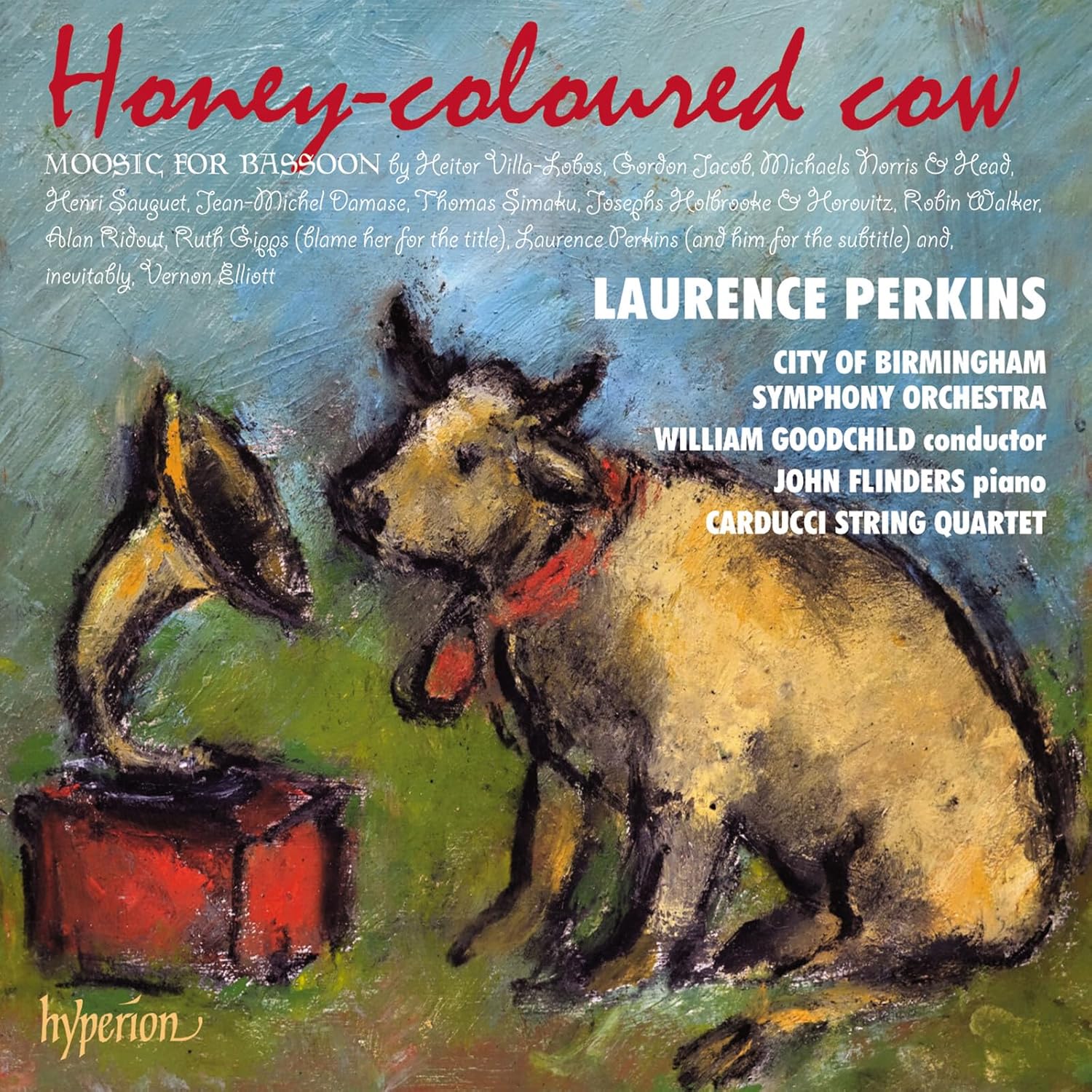

Honey-coloured cow Laurence Perkins (bassoon), with John Flinders (piano), Carducci String Quartet, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra/William Goodchild (Hyperion)

Honey-coloured cow Laurence Perkins (bassoon), with John Flinders (piano), Carducci String Quartet, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra/William Goodchild (Hyperion)

There’s a distinct lack of solo bassoon content on my CD shelves so this entertaining album has plugged a handy gap. Veteran British bassoonist Laurence Perkins’ sixth album for Hyperion explores the instrument’s expressive potency, poetry jostling space alongside humour. Take the title track, Ruth Gipps’ little bassoon and piano duet a winning portrait of a cow mooching about, the final bars including a realistic moo. Compare its gruff charm with the heart-stopping “Barcarolle” for bassoon and harp by French composer Henri Sauget, Perkins singing out over a soft arpeggiated accompaniment. It’s delicious, as is “Automne” by Jean-Michel Damasse. French composers invariably wrote idiomatically for wind instruments: you think of sonatas by Saint-Saëns and Poulenc, or the solos for bassoon and cor anglais in Ravel’s G major Piano Concerto.

The most substantial work on the disc is the closer, the Ciranda das sete notas composed in the early 1930s by Villa-Lobos, scored for bassoon and string orchestra. A bright opening gives no hint as to how introspective the music becomes in a slow central section, though the closing paragraph is upbeat. My favourite work on the disc is a delightful Suite for Bassoon and String Quartet by Gordon Jacob, an incredibly prolific 20th century British teacher and composer who really should be better known; think Malcolm Arnold (one of Jacob’s many pupils) with fewer jokes. This four-movement work is a delightful work, a tiny “Elegy” really plumbing the depths. There’s lots more here: pieces by Joseph Holbrooke, Alan Ridout among the standouts, plus some works for bassoon quartet. Vernon Elliott’s Ivor the Engine will strike a chord with listeners of a certain age, and there’s Joseph Horovitz’s Rumpole of the Bailey theme too. Beguiling stuff, brilliantly recorded and played.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

Add comment