Classical CDs: Bells, birdsong and braggadocio | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs: Bells, birdsong and braggadocio

Classical CDs: Bells, birdsong and braggadocio

British contemporary music, percussive piano concertos and a talented baritone sings Mozart

Thomas Adès, Oliver Leith, William Marsey: Shanty, Aquifer et al Hallé Orchestra/Thomas Adès (Hallé)

Thomas Adès, Oliver Leith, William Marsey: Shanty, Aquifer et al Hallé Orchestra/Thomas Adès (Hallé)

This album on the Hallé’s own label, rounds up recent works by Thomas Adès, alongside pieces by two British composers he has championed, Oliver Leith and William Marsey, all conducted by Adès himself. The first two Adès pieces both date from 2020, that year of uncertainty and cultural suspension. Shanty has an appropriately tentative air, mechanical lower plucked strings are set against sliding upper strings in a hypnotic web, repetitive but never quite repeating, eventually sliding down to the depths like a drowning ship. It’s sombre listening. Dawn is subtitled “Chacony for orchestra at any distance”, and was premiered at the audience-less 2020 Proms, by players dispersed around the Albert Hall. The sparse orchestration has a circling, repeating bass line featuring harp, gong and cimbalom, with solo instruments adding melodic commentaries. It is, again, quite bereft in tone, but has a defiant beauty, with Adès ear for sonority as keen as ever.

The breezy fanfare for 14 trumpets Tower – for Frank Gehry – is Adès in more expansive, public mode, with some of the nods to minimalism that can be heard in Dawn, and other recent pieces like Dante. It is spectacularly well played, gleaming like the stainless-steel clad building in France it was written to celebrate. The 17-minute Aquifer is the biggest piece on the album, and the most recent. Commissioned for Sir Simon Rattle’s first season at the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, it is a return in some ways to the drama of earlier pieces like Polaris or Tevot, dense and knotty, maybe with hints of Tippett or Henze. The playing is assertive and authoritative, the music developing with a geological deliberation and inexorability. It will take a few more listens to get the full measure of it, but I will certainly give it those listens.

William Marsey’s Man With Limp Wrist (premiered in 2023) is in eight short “scenes”, each based on oil paintings by Salman Toor. And just as the paintings reference Old Masters, so too does Marsey’s music, most notably Bach’s Passion chorales. The second movement recalls Holst in its folky swing, and elsewhere I heard nods to Vaughan Williams, Adès himself – and even Michael Nyman. It is an enjoyable listen, but I was wondering if it was going to be anything more than a sequence of events – and then the final, eponymous movement draws the threads together, the music poised and the orchestral playing sensitive and considered.

Where Man With Limp Wrist offers a series of glimpses of different worlds, Oliver Leith’s Cartoon Sun (2024) is more single-minded and unified. The sun is, to him, “a simplified complex thing” and his piece embraces simplicity, but simplicity with heft. There are bells, both quiet and riotous, a sunrise in which the orchestration glistens, and as the music takes its time, time itself gets suspended. It’s a very effective and thought-provoking piece, and a terrific album of new music. Bernard Hughes

Bartók: Piano Concertos 1-3 Tomáš Vrána (piano), Janáček Philharmonic Ostrava/Gábor Káli (Supraphon)

Bartók: Piano Concertos 1-3 Tomáš Vrána (piano), Janáček Philharmonic Ostrava/Gábor Káli (Supraphon)

That Bartók’s three piano concertos squeeze comfortably onto a single CD means that Concertos 1 and 2 retain a toehold in the repertoire despite being rarely performed live. Both works are fiendishly difficult, for the soloist as much as the orchestral players. I still bear the scars from taking part in a performance and recording of Concerto No. 2 some decades ago, where trying to nail the first movement’s interlocking brass and woodwind lines took hours of rehearsal time. Young Czech pianist Tomáš Vrána takes this music at a more relaxed speed than normal, though the ear soon adjusts. You really do hear everything, Gábor Káli’s Janáček Philharmonic Ostrava winds relishing Bartók’s knotty counterpoint, the brassy pileup at the close joyous and assertive. The central movement’s string writing is cool but beautiful, framing a pungent, central “Presto”. Vrána’s finale is as exciting as any I’ve heard, Bartók recycling his first movement material to ingenious effect, my favourite moment being the dreamy slowdown just before the concerto’s punchy close.

I’d suggest listening to No. 2 before tackling Bartók’s gnarly First Concerto, Vrána and Káli superb at bringing out this intimidating work’s cheekier, quirkier side. I’ve never heard so much melody in it, despite Vrána never smoothing over the rough edges. I suspect (and hope) that they’ve followed Bartók’s request, printed in early editions of the score, that the three orchestral percussionists should be placed directly behind the soloist. Certainly the assorted cymbals and side drums are wonderfully clear in this recording, the slow movement’s eerie closing minutes haunting. Raucous trombone glissandi signal a change of mood and the closing “Allegro molto” is a riot, one of Bartók’s most exhilarating finales, Vrána’s dazzling virtuosity always serving the music. After which, the late, mellow 3rd Concerto can sometimes feel like watered-down Bartók. Not here: Vrána’s sleeve note points out that all three works share the same musical elements, and that No. 3 shouldn’t be viewed as a step backwards. Birds and insects sing out in the “Adagio religioso” and the finale’s 3/8 dance is uniquely life-asserting; the soloist’s description of this movement as “an intoxicating dance with death itself” doesn’t ring true with me. These are marvellous, invigorating works. I’ll hang onto the old DG Géza Anda set as my reference version, but Vrána’s cycle is a brilliant modern alternative, beautifully engineered.

Mahler: Symphony No. 9 Park Avenue Chamber Symphony/David Bernard (Recursive Classics)

Mahler: Symphony No. 9 Park Avenue Chamber Symphony/David Bernard (Recursive Classics)

Don’t be misled by this group’s title. I’ve heard two recordings of Klaus Simon’s unexpectedly impressive chamber version of Mahler’s 9th and this new recording isn’t another one. David Bernard’s Park Avenue Chamber Symphony is 90 strong here, the conductor keen to stress that his group isn’t a chamber ensemble but a full-size outfit “striving for a transparency that reveals the contrapuntal texture of Mahler.” What we hear doesn’t sound small, in other words, though the strings are leaner and don’t occlude what’s happening in Mahler’s wind writing. Highlighting inner detail at the expense of momentum is an easy trap to fall into, but Bernard avoids it, his tempi flowing but unhurried. Subtly emphasising the rippling viola motif in the opening bars works for me, hinting at what lies beneath the long first movement’s serene beginning. Bernard makes sure that we notice the same sextuplets played by clarinets when the music recovers after the third big collapse. That recapitulation, urgent and passionate, is deeply moving here, relief, joy and regret perfectly balanced.

The inner movements are shrewdly handled: the Ländler heavy-footed but affectionate, Bernard’s low brass enjoying their moment in the sun. The “Rondo-Burleske” is raw and exciting, the ensemble pushed to the limit in the closing pages but hanging together. And I like Bernard’s emotionally-charged, perfectly paced “Adagio”, the string sound rich and full, Mahler’s wind and brass solos beautifully served. Mahler’s long, slow fade is immaculately handled, upper strings acquitting themselves beautifully. I’ve a soft spot for accomplished performances from unexpected sources, and this Mahler 9 is well played, handsomely engineered and emotionally satisfying. The sense of commitment, of affection for the score, shines through, and this is one of the best Mahler 9s I’ve heard in several years. Do investigate.

Andrè Schuen: Mozart - Operatic arias and duets, Lieder Andrè Schuen (baritone), Daniel Heide (fortepiano, piano), Nikola Hillebrand (soprano), Avi Avital (mandolin),Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg/Roberto González-Monjas (Deutsche Grammophon)

Andrè Schuen: Mozart - Operatic arias and duets, Lieder Andrè Schuen (baritone), Daniel Heide (fortepiano, piano), Nikola Hillebrand (soprano), Avi Avital (mandolin),Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg/Roberto González-Monjas (Deutsche Grammophon)

Andrè Schuen is a great Mozart baritone at the top of his game. As this review goes out, Schuen, originally from Südtirol/Alto Adige, is in the middle of a run of performances as Don Giovanni in Aix with Simon Rattle. He owns this repertoire, and that’s the point of DG having made the album. I can't help thinking back to another Aix Mozart baritone, Olaf Bär. He made an album of similar repertoire in Dresden and was duly praised for his "stylised bonhomie" and "flexibility". But that was in 1988, in the final months of the GDR and VEB/ETERNA, and Olaf Bär was at the tender age of 30; Schuen is now 41, so what one can appreciate on this album is quite how sung-in, how lived, how familiar, how enjoyable every twist and turn of the Mozart baritone roles is. All the authority, the charisma, the swagger just flow.

Furthermore, as the promotional materials stress, how emotionally right, how biographically consistent, what a great story it is for Schuen to have gone back to the source, to the city and the place where he did his studies – to Salzburg and to the Mozarteum itself – to make this album. But, and it feels almost churlish to dwell on it, there are problems. The main one is that the orchestral support can at times be distinctly ropy. Schuen launches into “Non più andrai” with his winning confidence and glorious braggadocio, but when the first violins of the Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg under new chief conductor Roberto González-Monjas respond to him with their first bunches of semi-quavers, there’s not much that engineer/producer Michaela Wiesbeck can do to disguise the fact that what we hear is a vague "effect" rather than what the ear expects in Mozart, a properly shaped and defined phrase. And I found the sound that those same first violin players make in the opening melody of “Der Vogelfänger …” from The Magic Flute embarrassingly undernourished.

The album's twenty tracks include other repertoire beyond the operatic realm, and here we find both highlights and low-points. The song “Abendempfindung” from 1787 is a gem, a beautifully paced and shaped account, with Schuen's regular Lieder-pianist Daniel Heide. On the other hand, their performance of the late masonic cantata Die ihr des unermesslichen Weltalls Schöpfer from 1791 feels pale and almost uncommitted - particularly when compared to the version by Schuene’s teacher Wolfgang Holzmair with Imogen Cooper. I wasn’t convinced by the performance of the concert aria “Mentre ti lascio” at all. Firstly because González-Monjas’s pacing and shaping appear haphazard, as if the work is unfamiliar, and secondly because the aria is clearly listed in Köchel’s catalogue as being written for a bass voice, and Schuen’s lower register here feels underpowered. This recording stimulates the appetite to see and hear Andrè Schuen live, in the Mozart operatic repertoire he absolutely owns. If only DG could have made a better album. Sebastian Scotney

Stravinsky & Ravel: The Rite of Spring/Ma Mère l’Oye Pavel Kolesnikov & Samson Tsoy (piano duet) (Harmonia Mundi)

Stravinsky & Ravel: The Rite of Spring/Ma Mère l’Oye Pavel Kolesnikov & Samson Tsoy (piano duet) (Harmonia Mundi)

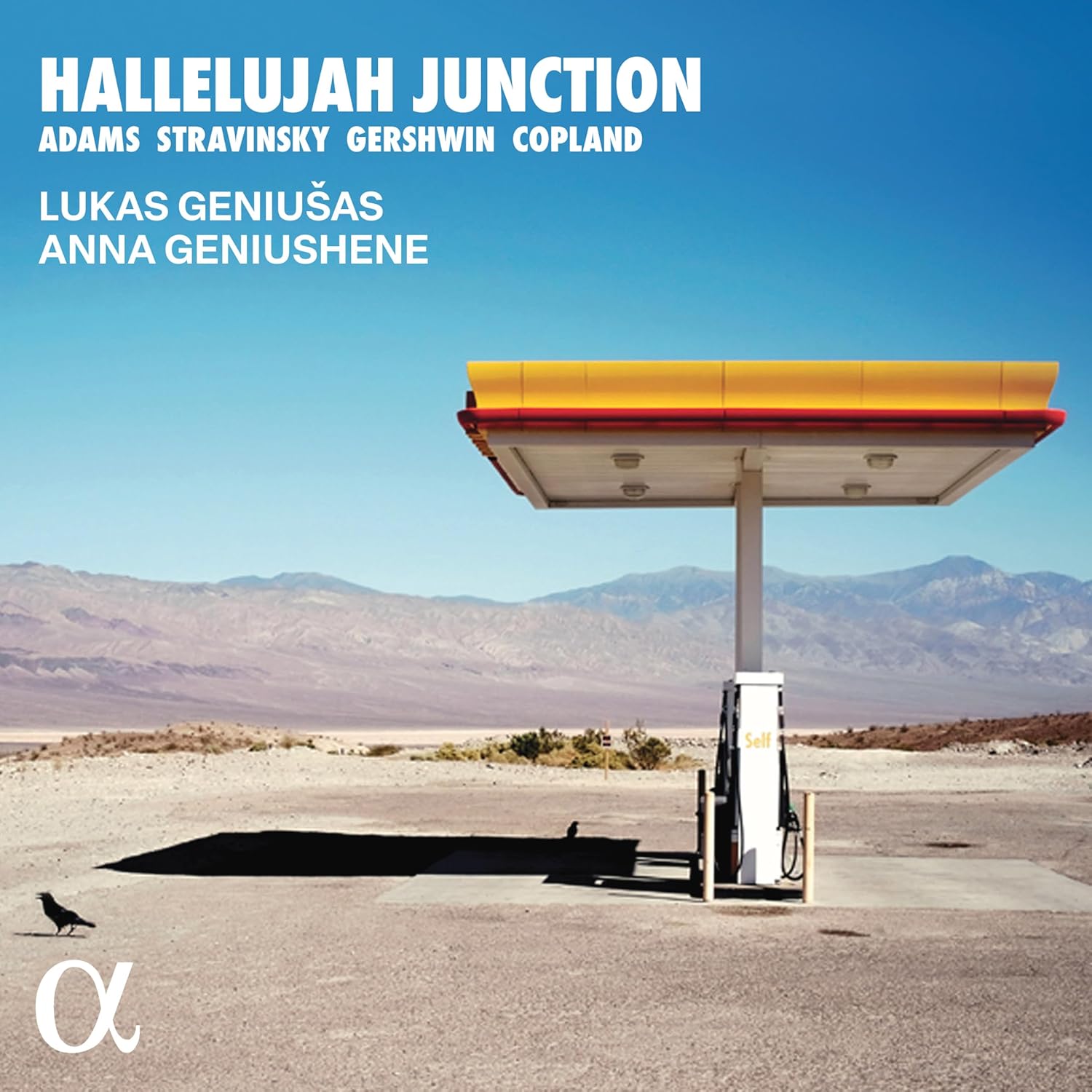

Hallelujah Junction – music by Gershwin, Stravinsky etc Lukas Geniušas and Anna Geniushene (piano duo) (Alpha Classics)

I’m a Stravinsky nut and for me The Rite of Spring has been the piece, since I discovered it as a teenager. But I actually heard the piano duet live before I heard it with orchestra, and have always had a soft spot for it. The piano’s attack makes the rhythms even more punchy, and the loss of orchestral coloration allows for the fearsome harmonic crunches to barrel through. This version, by Pavel Kolesnikov and Samson Tsoy, really goes out of its way to make a virtue of being a piano duet, rather than just a monochrome shadow of the original. They have a rhythmic precision in the “Introduction” that gives it a brilliant “wonky-clockwork” aspect. They take the “Augurs of Spring” at an insanely fast tempo – faster than an orchestra could ever manage – to give it an exhilarating forward momentum. And the “Spring Rounds” are heavily pedalled, setting up a gauzy, echoey haze around the notes, like mist rising over the steppe. A piano duet is never going to have the sheer heft of the orchestra in passages like the “Dance of the Earth”, although they give the keyboard a fair old pounding, but delicate passages like the introduction to Part 2 and the “Mystic Circles” are gorgeously played, making light of the problems of co-ordination and the knitting together of the players’ four hands.

There are no similar technical challenges in Ravel’s Ma mère l’Oye, which is simplicity itself. So what makes in an appropriate companion piece? The players argue in their liner note that “purity is the keyword here. Emotionally and aesthetically, the two pieces are exact opposites, but in both of them, the complex effects and lush sonorities are sacrificed in favour of the most essential.” If The Rite is as dissonant, violent rhythmically disrupted as it’s possible to be, the Ravel is consonant, calm and ordered – with any hint of disorder well out of sight. “Petit Poucet” is brisk and unsentimental, the middle section of “Les Etretiens de la Belle et de la Bête” the nearest we get to being unsettled, and even that soon passes. Only the finale left me a bit nonplussed: taken very slow, with washy pedalling, it seemed out of keeping with the spirit of the rest, exquisitely played as it undoubtedly is.

Where Kolesnikov and Tsoy share a keyboard, Lukas Geniušas and Anna Geniushene have a piano each in their recital disc named Hallelujah Junction, after the John Adams work with which they finish. If The Rite is my number one Stravinsky, the other two in my top three would be the Symphony of Psalms and the Concerto in E-flat “Dumbarton Oaks”, and, as with The Rite, the composer’s own two-piano version gives a fresh perspective on the piece. So I was eager to hear this new recording. Dumbarton Oaks is a neoclassical take on Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, but with everything – rhythm, harmony – a few degrees off true. It is a humble piece, but faultlessly conceived and something I never tire of. But to my disappointment, Geniušas and Geniushene didn’t convince. Their start is too bombastic, and the first movement fugue feels laboured. The second movement is more the thing at the start, with a Mozartian grace – but even then as the movement proceeds, the decorative embellishments are front-and-centre instead of commenting from a distance. The final movement is better, tense and edgy, but the whole thing still oversold, the finely crafted music put over with unnecessary forcefulness. I would recommend Alexei Lubimov and Slava Poprugin’s account, also on Alpha Classics, as preferable.

Where Kolesnikov and Tsoy share a keyboard, Lukas Geniušas and Anna Geniushene have a piano each in their recital disc named Hallelujah Junction, after the John Adams work with which they finish. If The Rite is my number one Stravinsky, the other two in my top three would be the Symphony of Psalms and the Concerto in E-flat “Dumbarton Oaks”, and, as with The Rite, the composer’s own two-piano version gives a fresh perspective on the piece. So I was eager to hear this new recording. Dumbarton Oaks is a neoclassical take on Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, but with everything – rhythm, harmony – a few degrees off true. It is a humble piece, but faultlessly conceived and something I never tire of. But to my disappointment, Geniušas and Geniushene didn’t convince. Their start is too bombastic, and the first movement fugue feels laboured. The second movement is more the thing at the start, with a Mozartian grace – but even then as the movement proceeds, the decorative embellishments are front-and-centre instead of commenting from a distance. The final movement is better, tense and edgy, but the whole thing still oversold, the finely crafted music put over with unnecessary forcefulness. I would recommend Alexei Lubimov and Slava Poprugin’s account, also on Alpha Classics, as preferable.

Fortunately there are other things to enjoy on this disc of mainly American music, although with some of the same reservations. Gershwin’s Cuban Overture kicks things off, where the loud-and-proud playing is more fitting, the syncopations emerging from the bass with real bounce. But as with the Stravinsky, I’d have welcomed more dancing lightness, more openness to the good humour of the music.

Leonard Bernstein’s arrangement of Copland’s El Salon Mexico fares better, the brittleness of the sound and the briskness of the rhythms working well, in contrast with quiet moments of introspection. And there is a generally softer approach to Colin McPhee’s gamelan-inspired Balinese Ceremonial Music of 1934, a fascinating precursor of the minimalism of the 1960s. The players capture the ritualistic character, and layer the textures nicely. All these strands come together in the closer, Adams’s Hallelujah Junction, by far the best thing on the album. Here the brashness of the playing fully in accord with the music, the extrovert character fitting the players’ touch and there is a genuine excitement in the outcome. Bernard Hughes

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

Add comment