Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness | reviews, news & interviews

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

I recently heard a BBC Radio 4 presenter use the troubling phrase: "Not everyone agreed on the reality of that." Once the domain of Andre Breton’s Manifeste du surréalisme, such sentiments are now alarmingly commonplace: part and parcel of the BBC’s increasingly unhinged approach to impartiality.

Poets have always wondered and worried about this, theirs being a world poised at the edge of meaning. Tom Raworth is no exception – he may, in fact, be exemplary: "if the rhetoric be false should not blind you to if the rhetoric be true"; "our knowledge is as the memories of the blind"; "Journalism: if you know the truth with what do you ‘balance the news'?" These lines, written all the way back in the 1970s, are a proleptic satire on the above BBC guff. They are also fired with Raworth’s particular – and particularly sharp – lyric imagination: bitterly ironic, wittily earnest, and always doggedly pursuing the "true centre, where art is pure politics".

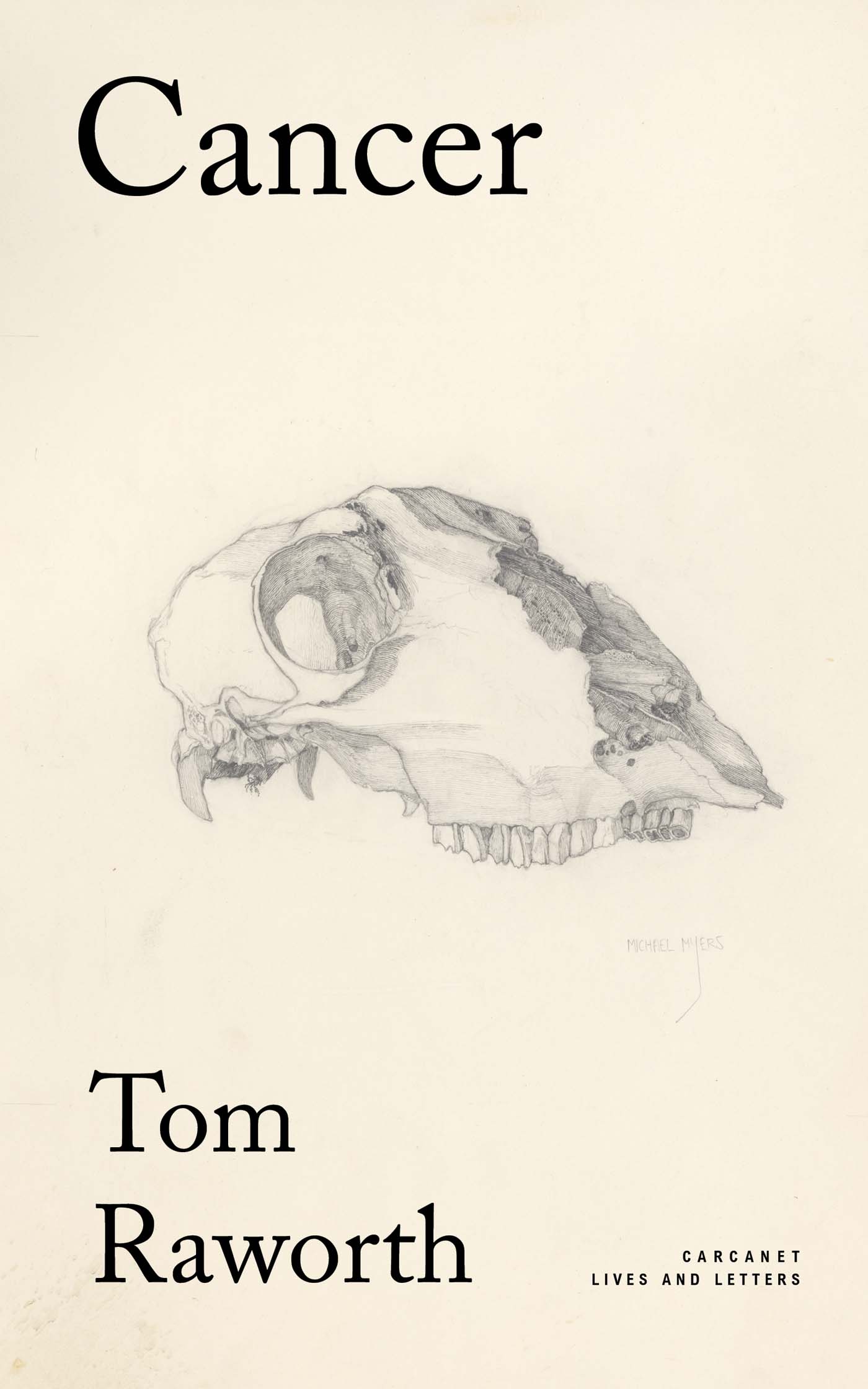

Each of these quoted fragments comes from "Journal", a diaristic composition that forms the centre section of Cancer, published this year by Carcanet. The other two sections are "Logbook", a difficult-to-describe prose-work satirising expedition narratives, and "Letters from Yaddo", a sequence of epistles sent by Raworth to fellow poet, Ed Dorn.

Press releases and website-descriptions refer to Cancer as "Raworth’s 'lost' book". The scare-marks tell us it wasn’t so much lost as temporarily misplaced: originally set for publication with Frontier Press in 1973, the typescript was returned to Raworth after Frontier went bust and "Logbook" found life as a standalone volume with Poltroon Press in 1976. Revised iterations of "Journal" and "Letters from Yaddo" were published in the 1980s, but are here reinstated in their original tripart form.

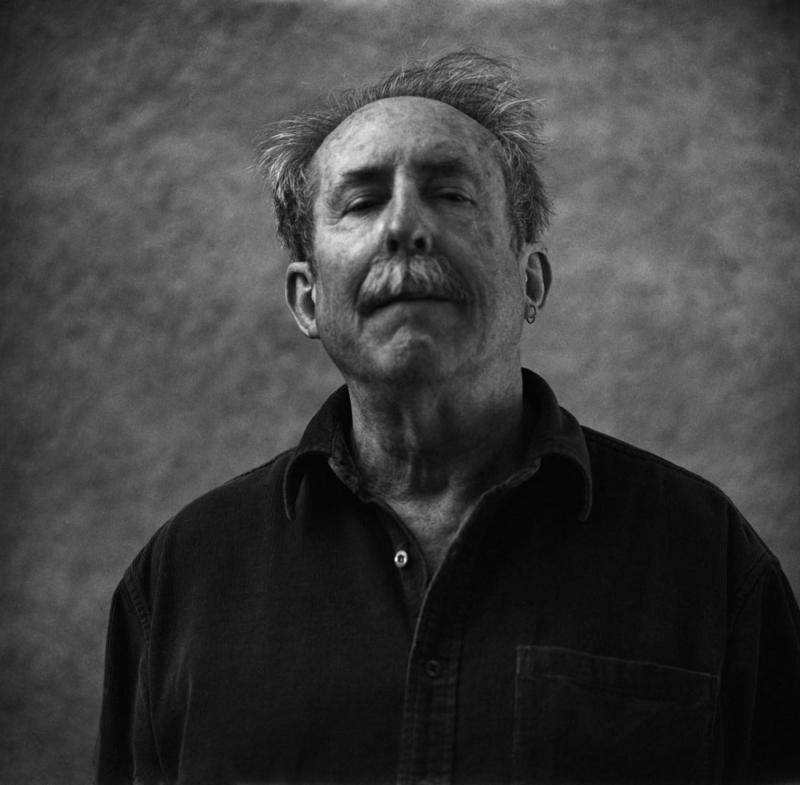

It is a very welcome re-addition. Raworth died in 2017, leaving behind over 40 books of poetry, and various other kinds of writing (frequently unclassifiable). It’s therefore a great happiness to read something new(-ish) that reconfirms Raworth’s standing as one of the great lyric poets. Every one of his publications tested the limits of what a poem could – or should – be. His debut, The Relation Ship (1966) exploded the text’s typographic stability to create entropic constellations of wordplay. 1984’s Heavy Light thinks seriously, and with great irony, about poetry’s brief power. (The poem "Read Me", for instance, bears only one line: "Thanks".) Elsewhere he works in exhaustive lists – always at top speed. That is, Raworth shreds rather than rests on laurels, continually critiquing his own expressiveness: his works are largely impossible to quote effectively due to either their radical length or restless mise-en-page; the poems flash across the page, glitching, always out of hand, going nowhere, falling apart, or combusting; they conspire with you, make fun of you (but never take you for granted). Carcanet’s Collected Poems stands at 640 pages. It is telling that most inclusions are extracts from longer, unmanageable works: these are poems living on the page’s edge.

It is a very welcome re-addition. Raworth died in 2017, leaving behind over 40 books of poetry, and various other kinds of writing (frequently unclassifiable). It’s therefore a great happiness to read something new(-ish) that reconfirms Raworth’s standing as one of the great lyric poets. Every one of his publications tested the limits of what a poem could – or should – be. His debut, The Relation Ship (1966) exploded the text’s typographic stability to create entropic constellations of wordplay. 1984’s Heavy Light thinks seriously, and with great irony, about poetry’s brief power. (The poem "Read Me", for instance, bears only one line: "Thanks".) Elsewhere he works in exhaustive lists – always at top speed. That is, Raworth shreds rather than rests on laurels, continually critiquing his own expressiveness: his works are largely impossible to quote effectively due to either their radical length or restless mise-en-page; the poems flash across the page, glitching, always out of hand, going nowhere, falling apart, or combusting; they conspire with you, make fun of you (but never take you for granted). Carcanet’s Collected Poems stands at 640 pages. It is telling that most inclusions are extracts from longer, unmanageable works: these are poems living on the page’s edge.

For my money, Raworth’s greatest achievement is Ace (1974). Again, it evades easy description, and is best experienced first-hand, but essentially it’s a columnar sequence of short, unpunctuated and uncapitalised lines, frequently pared down to single words – or even letters:

There is no way to tell where one thought ends and another starts (again, making it difficult to quote). It is a piece of acoustic-pronominal doodling of the highest seriousness, spinning around the "i" that begins "it" and hiding in the centre of the "trinity", which for some is the centre of everything: that linguistically inexpressible concept of the one-as-the-multiple. For Raworth here, "i" – ever-uncapitalised, as though a change of case is wasted time – is the finite centre of that which is beyond length, before beginnings, and without end: this thing we call, disappointingly, the "self". Ace plays this kind of game repeatedly; as though it could have gone on forever: it’s a real intimation of immortality.

Raworth’s poetry always combines quickness and extensiveness like this. We find it all the way through Cancer in deceptive squibs like "line out of formlessness". This entire journal-entry is both an unfinished thought and an ars poetica: self-describing as much as self-abandoning. By this recursiveness, it repeatedly offers a way – or a line – out of the dead-end it creates: a happy paradox of indefinite length and seriousness.

Cancer shows, too, that Raworth can do it in prose. "Logbook", "Journal", and "Letters from Yaddo" are all primarily prose forms (though each bears irrepressible bursts of poetry), and each suggests Raworth could have been an equally devastating novelist, had he wished it. Take, for instance, one of the Yaddo letters, which describes Raworth’s experience of open-heart surgery:

A voice tells him to count backwards from ten. At once he feels wide awake, though his eyes are shut, and thinks ‘this is taking a long time to work.’ As he thinks ‘work’ he opens his eyes. There is an enormous weight on his chest. He is inside an oxygen tent. Eight hours have passed and the operation is over. He runs that thought through again: ‘this is taking a long time to work’. He can see no break in it.

Turning himself into third-person (most of the letters are first-person), Raworth can parody the out-of-body experience described by many surgical patients, explore the weird detachment of narrative voice, and become a subject of his own incisive observation. He returns, too, to the concern of so much of his poetry: the point at which one thought stops and another starts. "He can see no break in it." The hospital vignette describes, like Ace, various complications between states of being: between one experience and another, between life and death, between yourself and your self. The letters, using a variety of methods and modes, make up a serious prose-work of poetic thinking and is, in this, an invaluable document. Poems or prose, Raworth gets to the heart of the matter.

Or, as Ted Berrigan once wrote of Raworth’s poems: "they can’t help but be right." There is, indeed, a relentless pursuit of truthfulness present throughout Cancer, and it’s a privilege to see Raworth’s mind at work: "events have expanded further than language can explain in time"; "you / can’t / contra / dict / your / self"; "you can only use yourself in the most truthful way possible"; "If it’s done with truth and love and no wish to profit, in any sense, then it will take shape." The last of these is as close as Raworth will come to a manifesto – but already he’s moved on. Emily Dickinson wrote that "The Truth must dazzle gradually". For Raworth, it comes, again and again, in a blinding flash. He is a poet of great and serious truthfulness: a reality on which, I hope, we can all agree.

- Cancer by Tom Raworth (Carcanet, £12.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Add comment