Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness | reviews, news & interviews

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Ten years after it first opened Barrie Kosky's production still packs a hefty punch

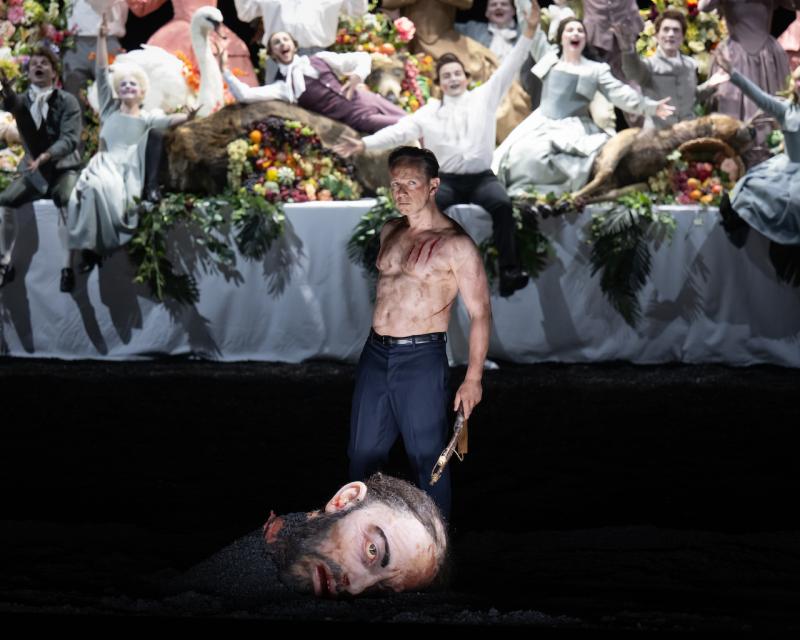

This thrilling production of Saul takes Handel’s dramatisation of the Bible’s first Book of Samuel and paints it in pictures ranging from grotesque exuberance to monochromatic expressionism. From the earliest flamboyant images, dominated by the disquieting presence of Goliath’s decapitated head, to an encounter with the Witch of Endor that has the starkness of Beckett, this tale of jealousy and betrayal grips you to the bitter end.

Barrie Kosky’s darkly subversive take first landed at Glyndebourne 10 years ago – then, as now, it featured Christopher Purves as the belligerent, mentally unstable King Saul and Iestyn Davies as David, the heroic young warrior who stokes his envy. Kosky is a director who has been defined by his bold intellectual experiments, and while some have – inevitably – divided opinion, this production was quickly hailed for its arresting aesthetic and searingly intelligent execution.

How is it faring a decade later? As someone who didn’t see it first time round, all I can report is that – in this revival prodution by Donna Stirrup – it seems to pack every bit as hefty a punch as that stone did when David first heaved it at Goliath. For a start, the oratorio feels particularly timely at a point when – on the world stage – we have no shortage of mad old men turned inside out by their determination to thwart any successors. Kosky’s not unwise enough to dabble in political specifics. What we have instead is an interpretation that deploys dark humour and surrealism to draw us into the depths of Saul’s psychological hell.

After the fleet-footed dispatch of the opening orchestral movements, Goliath’s decapitated head emerges from the darkness at the front of the stage. As the chorus of jubilant Israelites sing about their victory over the Philistines, a comically grotesque cornucopia is revealed. Katrin Lea Tag’s inspired design isn’t anchored in a specific period; the costumes are a mash-up of 18th century foppery and outfits that wouldn’t look out of place in a 21st century nightclub. Posed on flower-laden tables with white tablecloths, the chorus strikes different silhouettes as they sing, before leaping down to reveal a decorative carnage of deer and wild boar carcasses alongside stuffed ornamental birds. Iestyn Davies at first strikes a woebegone figure amid this scene of salacious bloodlust, half-naked and staggering, overwhelmed both by his recent achievements and the acclaim of the crowd. Yet the moment he responds to Saul’s question, “whose son art thou?”, the crystalline clarity of his countertenor voice stills the hyperactive crowd around him.

Iestyn Davies at first strikes a woebegone figure amid this scene of salacious bloodlust, half-naked and staggering, overwhelmed both by his recent achievements and the acclaim of the crowd. Yet the moment he responds to Saul’s question, “whose son art thou?”, the crystalline clarity of his countertenor voice stills the hyperactive crowd around him.

Even though his David is reluctant to accept the honours being offered to him, there’s a white-hot intensity to his singing that evokes the depth of pain that comes with attaining this victory. It’s clear that it’s this sense of his profound understanding of human suffering that will make him worthy as a leader. In the initial scene, it also makes him instantly magnetic both to Saul’s daughter Michal and his son Jonathan. In a brilliant bit of understated choreography, the latter, dressed in black, quietly goes and maps his body onto David’s as if they were soulmates from Plato’s Symposium.

The oratorio’s librettist, Charles Jennens, was famously exasperated with Handel for what he deemed excessive inventiveness for this work. In a letter, he declared that “Mr Handel’s head is more full of Maggots than ever,” as the composer splashed out on a “very queer Instrument which he calls Carillon” [a keyboard that rings bells] and “an organ of £500 price”. Yet despite tensions offstage, together they managed to produce a work of highly enjoyable psychological complexity. That’s clear both in the ebullient inventiveness of the music (the Carillon is particularly enjoyable) and in the subtlety of the different impacts that David has on Saul’s three children – while all of them end up championing him, the eldest daughter (Merab) is initially repelled and rejects him as a commoner.

Sarah Brady (pictured above) is superbly acidic as Merab, going from sharp-elbowed haughtiness – her distinctive soprano marked by biting consonants – to outraged dignity as she realises her father is more worthy of contempt than David. Soraya Mafi’s Michal is as spirited as she is loyal, the pure beneficence of her voice as she urges David to calm Saul’s rage with his lyre is in stark contrast to her whoops of unadulterated joy when she realises she can have sex with him. As Jonathan, tenor Linhard Vrielink is valiantly warm and empathetic in a role in which ultimately he must sacrifice himself to others’ interests. Yet it is inevitably Purves’s tortured bass-baritone Saul (pictured above, front) who draws us in with his capitulation to dark emotions that he finds himself less and less able to control. After the colourful maximalism of the first act, we find ourselves in a starkly minimalist setting in which the tables with white tablecloths are positioned in parallel with a dark chasm between them. As the chorus sings about “envy”, Saul’s head – once covered with long curly hair – emerges bald and blinking as disembodied hands run like fleshy spiders across his scalp.

As Jonathan, tenor Linhard Vrielink is valiantly warm and empathetic in a role in which ultimately he must sacrifice himself to others’ interests. Yet it is inevitably Purves’s tortured bass-baritone Saul (pictured above, front) who draws us in with his capitulation to dark emotions that he finds himself less and less able to control. After the colourful maximalism of the first act, we find ourselves in a starkly minimalist setting in which the tables with white tablecloths are positioned in parallel with a dark chasm between them. As the chorus sings about “envy”, Saul’s head – once covered with long curly hair – emerges bald and blinking as disembodied hands run like fleshy spiders across his scalp.

There are shadows of King Lear, Nosferatu, and even Sarah Kane’s Blasted, as Kosky’s production shows how Saul’s paranoia takes him into a dimension where he can no longer distinguish between what is real and what is not. Throughout, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment – led by Matthew Truscott – excavates both the decadent joys and sinister undertones of Handel’s richly woven score. Both the original choreographer, Otto Pichler, and the revival choreographer, Merry Holden, should be commended too for presenting a bright palette of movement that ranges from witty groin thrusts to Saul’s staggering descent into oblivion. A decade on, Kosky’s production continues to mark itself out as a vital, visually arresting and important work in Glyndebourne’s ever evolving repertoire.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Add comment