theartsdesk Q&A: director Andreas Dresen on his anti-Nazi resistance drama 'From Hilde, with Love' | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: director Andreas Dresen on his anti-Nazi resistance drama 'From Hilde, with Love'

theartsdesk Q&A: director Andreas Dresen on his anti-Nazi resistance drama 'From Hilde, with Love'

The East German-born filmmaker explains why his biopic of the activist Hilde Coppi isn't bound to the 1940s

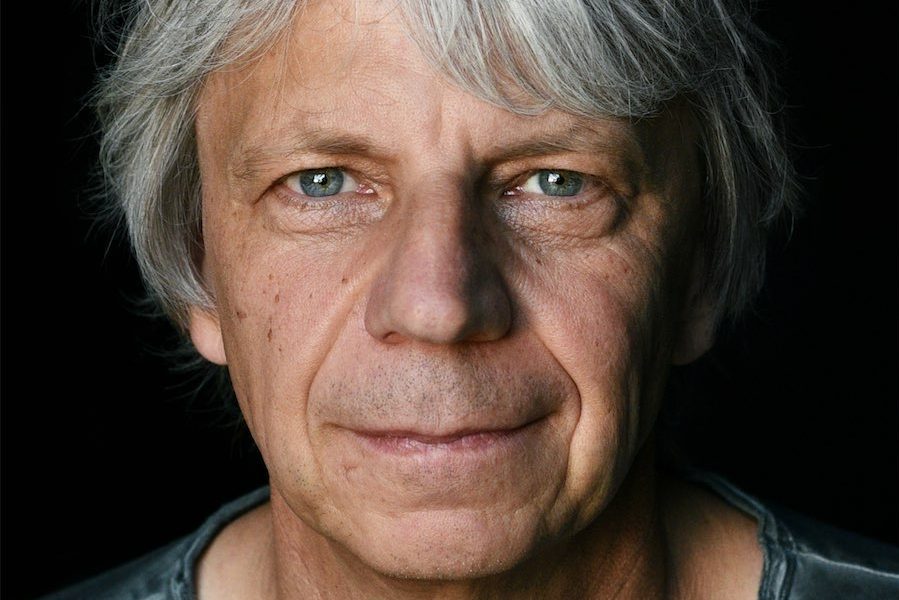

Andreas Dresen directs socially engaged realist films that invariably relay personal and political messages; the result can be tough but is usually tender at heart.

His Dogme 95-influenced Grill Point (2002), winner of the Silver Bear in Berlin, follows two couples in crisis. Cloud 9 (2008) and Stopped on Track (2011), both Cannes prize-winners, addressed sex in old age and dying respectively. Gundermann (2018) is a biopic of the East German singer-songwriter and Stasi informant Gerhard Gundermann. The real-life Guantánamo drama Rabiye Kurnaz vs George W Bush (2022) depicts the eponymous Turkish woman’s struggle to free her illegally imprisoned son.

From Hilde, With Love, Dresen’s new film, tells the story of the anti-Nazi Red Orchestra activist Hilde Coppi (1909-43), played by Babylon Berlin star Liv Lisa Fries. Coppi was pregnant when she was arrested, along with her husband Hans (Johannes Hegemann), by the Gestapo in 1942. Coppi’s offence against the Hitler regime included broadcasting messages to the Soviets and passing on information broadcast by Radio Moscow to relatives of German POWs, which contradicted the Nazi propagandists’ insistence that Russia summarily executed prisoners.

Sitting down to discuss the film after it premiered at last year's Berlinale, Dresen talked about courage, resistance, and retaining decency in the face of danger. (Pictured below: Liv Lisa Fries and Johannes Hegemann)

PAMELA JAHN: From Hilde, With Love has a different visual quality to most films set in. World War II Germany. How did you approach it?

PAMELA JAHN: From Hilde, With Love has a different visual quality to most films set in. World War II Germany. How did you approach it?

ANDREAS DRESEN: There is something like a Nazi cinema canon in Germany, with an unwritten law that dictates how films that are set during the war should look and feel: sepia tones, dramatic music, polished boots, waving black, red, and white flags. We wanted to avoid all of that yet still be historically accurate. We just didn't want to create a feeling that implies we're looking back to a distant past, but rather that we're observing characters who have certain things in common with young people today. The result was a kind of mixing in the set design, especially in the costumes and hairstyles.

Hilda Coppi is what people might call a decent person. Who or what shaped your personal value system?

People like Lothar Bisky, the former rector of the Babelsberg Film University, who later became head of the PDS [Party of Democratic Socialism] for some time in the 1990s, before he moved on to the Left Party. He was a highly decent person, someone who didn't shy away from risking a great deal in his position in East Germany. For example, he prevented my fellow student Andreas Kleinert and me from being expelled from school because we had made films that did not fit into the political system at the time. It's easy to speak up when you have someone to safeguard and defend you. Bisky was one of those people. No one protected him.

What did you learn from him?

Courage in everyday life. Just like you can see in Hilde and Hans. The question is always the same: Am I prepared to conform to a political system that I don't agree with? Or when is the moment I rebel and resist against the state? Everyone must find the answer for themselves.

You decided to tell From Hilde, With Love from a private perspective. You play down Hilde’s political motives.

But it's there. You don't make a political decision by declaring it being political; it becomes political through the action. For example, when Hilde talks to Hans about what it means to transmit radio messages about Nazi troop movements to the Soviet Union, information that came from Harro Schulze-Boysen in the Reich Air Ministry – that is a dangerous action. Another is when Hilde listens to the Heimatpost programme on the radio, where German war prisoners could send messages to their families at home to let them know they are still alive. Listening to foreign radio stations was strictly forbidden and led to severe consequences, the death penalty in this case. Hilde’s decision to write letters to these relatives is also political. (Pictured below: Andreas Dresen; photo: Palace/André Röhner)

Would you describe Hilde as truly political?

Would you describe Hilde as truly political?

She was certainly not apolitical, though she was not a class warrior who read the Communist Manifesto and then marched off with her fist raised. She had a keen instinct for what is right and what is wrong. Hilde is more of a silent heroine, and they are sometimes more important than the ones who shout and scream.

The film portrays the Nazis as ordinary Germans, which makes their actions more perfidious.

Yes, we mostly know them from films as thuggish SA and SS hordes. But I believe that even during that period, most of German society consisted of followers, of opportunists, and of those who simply obeyed the rules and played along. That is the foundation on which the violence of individuals or institutional violence grows, which is then expressed in the terrible execution of Hilde. This is only made possible by the silence of the masses. I find them interesting because, although their actions are no less terrible in their consequences, it is not so easy to distance oneself from them.

Why is the prison guard Mrs Kühn [played by Lisa Wagner] such an important character?

Anneliese Kühn is a historically documented person. In real life she was even more helpful than in the film. She smuggled things to the prisoners and supported them in other ways. In our version, she becomes more of a character who slowly develops a consciousness. At the beginning, she is a woman who constantly refers to the rules and seems to see her purpose in life in following them. Gradually, however, she gains a certain respect for Hilde. She sees how this young mother fights, how she stands up for her child, even behind bars. This respect grows into affection, and out of this affection she lets small rule violations slide. When she suddenly stops listening when Hilde tells her mother about her sentence, or when she unlocks the neighbouring cell for her.

Would you go so far as to say that Mrs Kühn begins to question the rules at that moment?

We know from Hannah Arendt’s book about Adolf Eichmann that he always claimed that he was only following orders and obeying rules. That's why he [didn’t think he was] guilty. But don't we always have a moral obligation to question the rules? That's the crux of the problem. And with Anneliese Kühn, this process seems to be slowly setting in. That fascinated me.

Why did you begin the film with Hilde's arrest?

When I first read the script, her story was still told chronologically. It divided the story into two parts. The first half was about Hilde and Hans’s love story and their resistance struggle, while the second half focused on Hilde's time in prison, the birth of her child, her inner maturation process during her imprisonment, and her execution…

And what bothered you about that?

I felt it would tear the film apart. Besides, the ending was incredibly bleak. By interweaving the different time levels, we tried to take some of the heaviness out of it. The love story is told backwards so that we can contrast the horror of death at the end with the hope of a new beginning. For me, mirroring the two levels also had the advantage that, amid the dreariness of everyday prison life, you always sense that there was a before, a freedom that was not only defined by struggle, but also by swimming with friends, eating ice cream together, and carefree days.

Was there enough reliable material about Hilde and Hans Coppi and the Red Orchestra resistance network for you to draw on?

Yes. The subject has been thoroughly researched by historians, including Hilde and Hans's son [Hans Coppi, Jr.], who has devoted virtually his entire life to writing this history. However, the documents found in the archives are mainly from the Nazis. We had access to the court records and, best of all, to the letters in which Hilde really comes across as a very real person. That's why we included her farewell letter in its entirety in the film. You can tell from the tone what a kind, touching person she was.

Law and justice are fundamental elements of your films. Does that have anything to do with your work outside of the film industry, for example your position as a constitutional judge in the German regional state of Brandenburg?

I held that position for 11 years and, during that time, I naturally dealt extensively with all kinds of legal issues. But it's not at all the case that my work at the court has directly influenced my film work. I was interested in the relationship between individuals and society before that. It's fascinating to see how I fit into a community as an individual without betraying my inner morality, my inner compass.

You can see that very clearly in my film about Gerhard Gundermann, who is completely at odds with the world he lives in. At the same time, he is treated as an outsider. He works for the Stasi and later becomes a target of surveillance himself. In Rabiye Kurnaz vs George W Bush, on the other hand, I was interested in the extent to which a single woman can rebel against the powers of this world to fight injustice. It's similar with Hilde. It's the same question that I always ask myself: How far can I influence the society I live in? Or let's put it even more simply: How can I make society a better place?

Was there a key moment when you thought, “I must do something now?”

1989 was a truly defining experience for me. On 10 November, the day after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I went to West Berlin with a friend, and we stood on this very wide section of the wall at the Brandenburg Gate. Suddenly, I realised that I could see my former home from a Western perspective. I thought, “You can walk through the gate!” Until then, it had always been the end of my world, synonymous with a border. I had simply never questioned it. But in that moment, everything turned upside down for me, and I knew that you should never accept things as they are, as God-given, but always try to look at them from a different perspective.

Unfortunately, very few people today still think that way. The majority feel that nothing can be changed.

Yes, and then people don't vote, which is where you start to make a difference. What's more, experience shows that not voting always plays into the hands of the wrong people. A democracy is only as good as those who stand up for it.

How do you respond to the accusation that films about Nazi resistance fighters make it easy for Germans to distance themselves from the question of guilt?

I strongly disagree. People who have retained their decency should be celebrated for their courage because they also serve as role models. That doesn't mean that the perpetrators are exonerated. Again, it depends on your perspective and on giving the victims their dignity. That's why it's important to tell the stories of these people, not only during the Nazi era – I would do it again and again.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

Weapons review - suffer the children

'Barbarian' follow-up hiply riffs on ancient fears

Weapons review - suffer the children

'Barbarian' follow-up hiply riffs on ancient fears

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Blu-ray: Two Way Stretch / Heavens Above!

'Peak Sellers': two gems from a great comic actor in his prime

Blu-ray: Two Way Stretch / Heavens Above!

'Peak Sellers': two gems from a great comic actor in his prime

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

Add comment